- Best Practices for Equipment O&M

-

O&M Best Practice Issue Discussions

- Advanced Maintenance Approach: Reliability Centered Maintenance

- Applying Key Performance Indicators

- Comprehensive O&M Program

- Contract Challenges and Improvements

- Cybersecurity for O&M Systems

- Existing Building Commissioning Procurement

- Healthy Building O&M

- Integrating and Analyzing Building Information to Support O&M

- Maintenance Approaches

- OMETA: An Integrated Approach to Operations, Maintenance, Engineering, Training, and Administration

- Prioritizing O&M Actions

- Re-tuning Buildings

- Tools

- Glossary

Prioritizing O&M Actions

O&M Best Practice Issue Discussion

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Discussion

- Solutions and Actions

- Prioritizing O&M Actions

- Establishing an O&M Vision

- Assessing and Adjusting O&M Activities

- Investing in Proactive Maintenance

- Additional Resources

- Definitions

- Sources of Information

Introduction

This Best Practice outlines a general process that operation and maintenance (O&M) departments follow when prioritizing their activities.

Effectively utilizing available resources is key to any field of management, and for facilities management personnel, this task involves prioritizing O&M actions. This is particularly relevant to the federal sector because managers for public facilities have historically faced limited or inadequate budgets for O&M activities; in the 1990s, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO; now the U.S. Government Accountability Office) documented these limitations and their associated adverse effects (GAO 1990; GAO 1991; GAO 1993; NRC 1998). However, resources are typically limited even in ideal circumstances, and effective prioritization is necessary to optimize the use of these resources. Furthermore, the federal sector is unique in that operating with limited resources for short periods of time is critical to success. In other words, federal facilities need to be resilient to the disturbances that will likely occur during an emergency event. If O&M actions are not adequately prioritized in preparation for these situations, the facility will likely fail in its mission.

This Best Practice provides resources to assist federal facilities (and energy) managers in improving their prioritization of O&M activities. While these managers are currently setting effective priorities for their O&M activities, this Best Practice will help them succeed in their stewardship of federal buildings by aligning terminology and processes used across various organizations as well as accelerating the propagation of more effective O&M management.

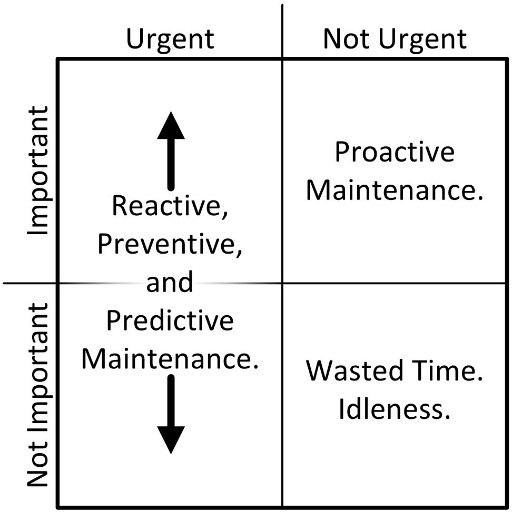

The key motivation behind any prioritization effort is captured in the Eisenhower Decision Matrix format, which categorizes actions according to (1) their importance and (2) their urgency. With this in mind, the purpose of prioritization is to focus resources on important activities, including those that are not necessarily urgent. Using the Eisenhower Decision Matrix format, Figure 1 shows the O&M Decision Matrix and places proactive maintenance in this important-but-not-urgent quadrant.

Reactive maintenance is inherently urgent because it is performed in response to a fault or failure that has already occurred. On the other hand, preventive maintenance (PM) is not inherently urgent, but urgency is added by scheduling PM activities; to complete the PM schedule on time, certain actions must be performed in the short term. Similarly, the inspections associated with PM activities are typically scheduled, and when the inspection indicates that maintenance is needed, this action becomes urgent. In contrast, neglecting PM will not result in immediate equipment failure, prolonged downtime, or in failure to meet a deadline. Nevertheless, PM includes some of the most important activities. For example, the PM and inspection schedules would not exist (and therefore there would be no urgency for preventive and predictive maintenance) unless the O&M program proactively generated schedules to periodically complete important maintenance activities.

Discussion

Consider the O&M decision matrix provided in Figure 1. Without any prioritization effort, O&M personnel will spend almost all their time and resources on urgent activities, but these activities will have varying degrees of importance. Urgent activities include responding to work orders (reactive maintenance) and carrying out scheduled PM and inspections (predictive maintenance). Many of these activities are indeed important, but a prioritization effort may reveal that many others are not as important as initially thought. However, evaluating the priority of these various activities is not possible unless a clear O&M vision is established; therefore, establishing this vision is the first step in the prioritization process. Because the O&M vision will vary widely from one facility to the next, each facility will set unique priorities. However, each facility manager may follow and iterate on a common, generalized process to set appropriate priorities.

Solutions and Actions

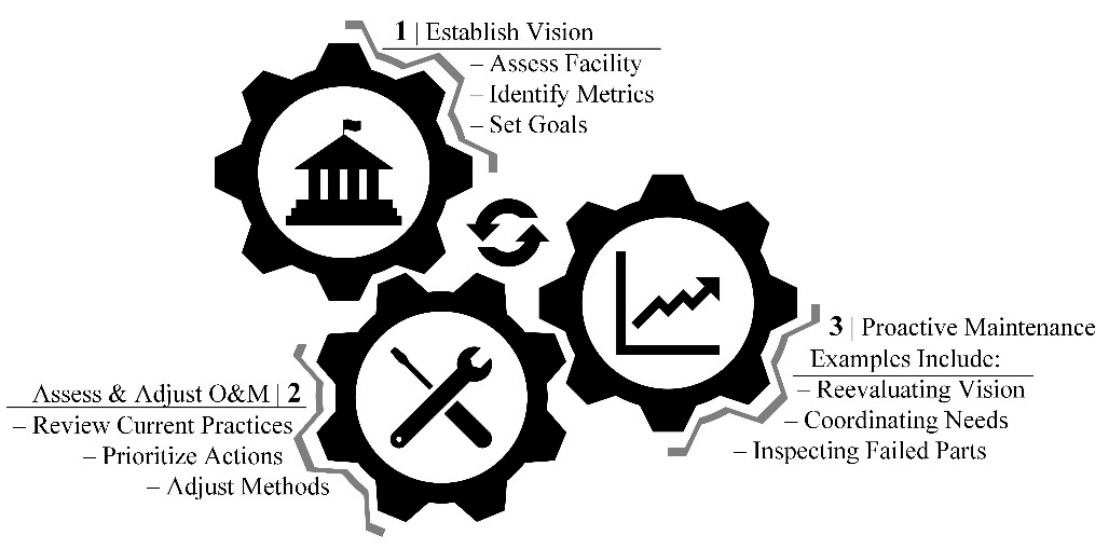

The fundamental three-step process for prioritizing O&M actions is summarized below and expounded on in the following sections.

Prioritizing O&M Actions

- Establish an O&M vision (Step 1).

- Assess and adjust O&M activities (Step 2).

- Invest in proactive maintenance (Step 3).

Having established the O&M vision (Step 1), current O&M actions should be assessed and adjusted as necessary (Step 2), and a portion of resources should be invested in proactive maintenance (Step 3). Proactive maintenance includes those important-but-not-urgent (Figure 1) activities that assure the future success of the O&M program. Actively investing resources in this category is essential because unless these actions are actively planned, urgent-but-less-important needs will soon consume the intended resources.

Establishing an O&M Vision

Defining goals and metrics (performance measures and indicators) is key to any prioritization effort, and in this context, establishing an O&M vision simply refers to the process of defining the goals and metrics relevant to a facility’s O&M. However, these goals must be aligned with the facility mission, so establishing a vision requires that the mission’s dependency on the various facility processes and systems is clearly understood. The impact that failure in systems and components may have on health and safety should also be considered. Furthermore, this process will be performed most efficiently and comprehensively when input is received from all building stakeholders.

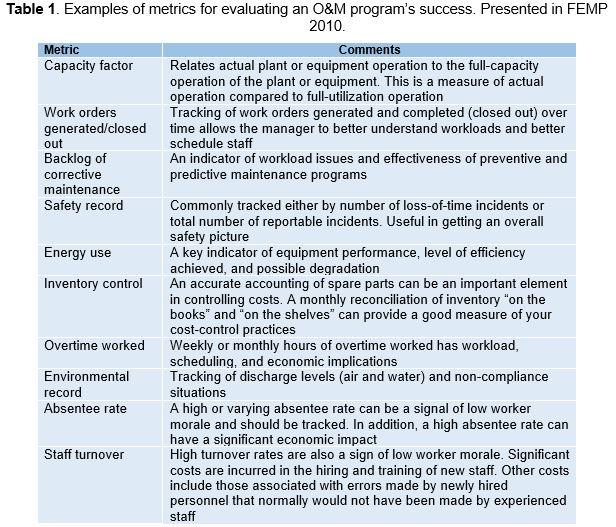

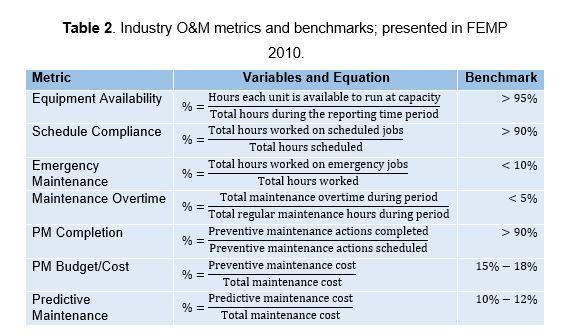

After establishing the impact that processes, systems, and components have on mission, health, and safety, the metrics that reflect success must be identified. In other words, how will success be measured? For example, if a certain system is critical to a facility’s mission, then the downtime for that system may be an appropriate metric that reflects the success of the O&M efforts. Several potential metrics are outlined in Operation & Maintenance Best Practices (FEMP 2010) and summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. However, the metrics chosen will be specific to a given facility and will often vary from those presented here.

Finally, having identified metrics that capture the success of the O&M program, goals must be set to both maintain success and improve deficiencies. An O&M vision is most effective when both short-term (e.g., 1year) and long-term (e.g., 5–10 year) goals are set. Goals should be quantified with identified metrics, be specific, and be realistic: S.M.A.R.T goals are Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic, and Time-based (Doran 1981). The goals for the O&M program must capture the criticality and priority of the various systems and must be coordinated across all building stakeholders; receiving input from all stakeholders is critical to obtaining the resources necessary for success.

Assessing and Adjusting O&M Activities

Establishing an O&M vision through quantifiable metrics and specific, realistic goals lays the foundation on which O&M activities are prioritized. This section discusses the process of assessing current O&M activities and adjusting these activities to align with the facility vision. It may be helpful to think of this process in three steps: (1) generate a list of both current and potential maintenance activities, (2) prioritize all activities based on how they align with the established site O&M vision, and (3) adjust maintenance activities to meet critical tasks most effectively.

The first step to assess O&M activities is to generate a list of current and potential maintenance activities. There will likely be a variety of activities, but these can generally be classified into three categories: reactive, preventive, and predictive maintenance. Reactive maintenance is the work performed in response to a failure and is often documented via a log of work orders. PM may generally be considered those actions that are scheduled and performed at regular intervals, and predictive maintenance includes tests, inspections, and the actions taken in response to the results. Generating a list of maintenance activities may include reviewing manufacturer recommendations and warranty requirements, present and historical work orders, the PM schedule, and regular tests and inspections. Many O&M programs use a CMMS that will alleviate much of the burden of obtaining this list of current practices. Still, care should be taken to avoid overlooking activities that are not captured by the CMMS. Also, the maintenance list must include potential activities such as those relating to newer equipment that have not been fully incorporated in the O&M program yet.

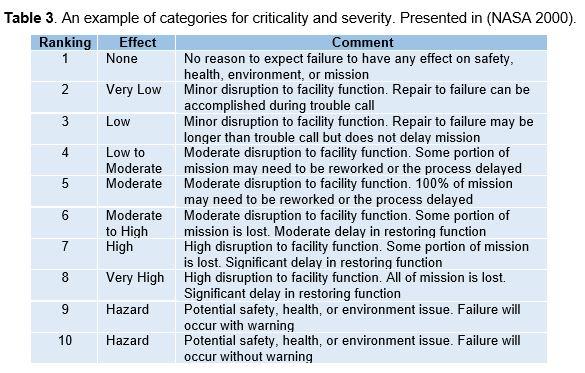

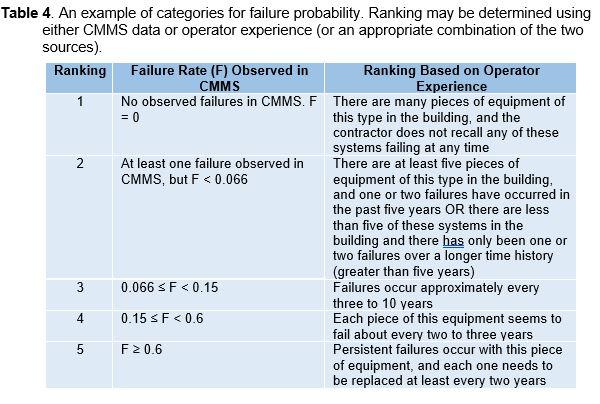

The priority of each activity in these three maintenance categories should be assessed based on their relationship to the O&M vision. The Reliability Centered Maintenance Guide for Facilities and Collateral Equipment published by NASA (NASA 2000) presents a scoring system (ranks 1 through 10) for the criticality of a system. These criteria are included in Table 3 and are strongly dependent on the facility mission. This is why the O&M vision must be established before prioritizing how critical each action is. In addition to the criticality of facility equipment, the probability of failure should also be considered in the prioritization process. Table 4 presents two methodologies for ranking the probability of failure; the first is based on CMMS data, and the second is based on operator experience (when CMMS data is not available). Together, Table 3 and Table 4 may be helpful in determining the priority of a given maintenance activity.

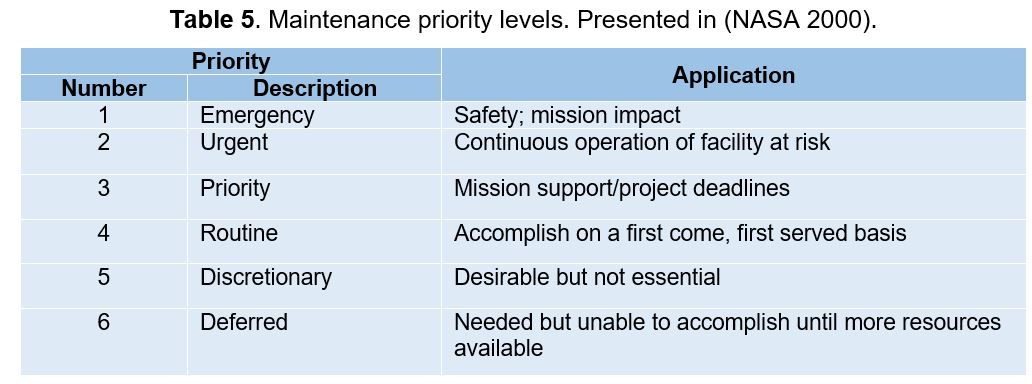

NASA’s guide also included a scoring system for maintenance priority levels (Table 5). While these three scoring systems may be helpful, facility managers should determine the scoring and prioritization methodology that is best suited for their facility. Note that this prioritization step is also an appropriate time to identify and remove maintenance activities recorded in the CMMS that may be outdated or unnecessary (perhaps relating to equipment that has been decommissioned).

The priority level score will then aid managers in making necessary adjustments to their O&M program. If high-priority (urgent or emergency) items are regularly addressed as part of reactive maintenance, then preventive or predictive maintenance solutions should be implemented. Distinguishing between whether a preventive or predictive solution is best centers on several factors, including whether an effective test or inspection method exists, the cost of the test or inspection, the criticality of the system in question, and how predictably the failure occurs. Also, some preventive and predictive maintenance activities may be better suited for a run-to-failure approach (reactive maintenance). For example, systems with low capital costs and for which failure will not affect the facility mission or occupant safety may be more cost effective to replace at failure than to expend resources during preventive and predictive maintenance tasks.

Investing in Proactive Maintenance

The third step in the generalized O&M prioritization process involves proactive maintenance. Proactive maintenance is a broad term intended to capture those activities designed to reduce future failures. Being future-oriented, these activities are never urgent but are among the most important for O&M success. The vast majority of O&M resources will be dedicated to completing the various reactive, preventive, and predictive maintenance tasks, and including this last step in the prioritization process is essential to magnify the few resources remaining.

Proactive maintenance has historically emphasized a technical approach to controlling future failures. When introducing the concept of proactive maintenance, NASA 2000 lists several of these technical solutions, including the following:

- Incorporating maintenance lessons learned in the design process

- Identifying the root cause by inspecting failed parts or performing a root cause failure analysis

- Improving repair specifications to eliminate underlying causes of failure.

These technical solutions are important for controlling future failures, and O&M managers should identify those practices that are most appropriate for their respective facilities. However, proactive maintenance involves more than technical solutions such as those outlined above. This Best Practice seeks to expand the view of proactive maintenance to include administrative strategies that are essential for controlling future failures. These essential administrative solutions may include the following:

- Clearly communicating O&M priorities to all building stakeholders

- Developing a reputation for dependability and trust

- Periodically reevaluating the O&M program and adjusting priorities (repeating the three-step prioritization process).

Proactive maintenance activities such as those listed above are certainly the least urgent O&M activities. However, they are among the most important. One of the greatest advantages of prioritizing actions within an O&M program is being able to save resources for these proactive activities. These are also the activities that may result in an expanded budget in the future; communicating the O&M needs and the mission’s dependency on O&M is essential to obtain future resources for O&M.

Conclusions and Next Steps

This Best Practice has briefly outlined a three-step process that facility (and energy) managers use to prioritize O&M actions (Figure 2). This process includes (1) establishing an O&M vision, (2) assessing and adjusting O&M activities, and (3) investing in proactive maintenance activities. Establishing a vision (Step 1) involves identifying critical systems for the facility mission, health, and safety, identifying metrics that reflect the success of the O&M program, and setting goals for these metrics. This is a necessary precursor to assessing and adjusting O&M activities (Step 2) because defining a vision establishes the criteria on which actions will be prioritized or scored. After prioritizing and adjusting the O&M program, investing in proactive maintenance activities (Step 3) is important because this assures the continued success of the O&M program. Proactive activities address future failures before they occur, thereby increasing O&M resources over time. As part of a proactive mindset, this process should be repeated periodically to assure the optimal O&M efforts are performed.

Prioritizing O&M actions requires a vision for the O&M program, and this necessitates buy-in from stakeholders. Perform a brief site assessment by considering the following question—do stakeholders approve of the site’s condition, reliability, and safety? The answers to this question (which will likely vary across the different stakeholders) will reveal the stakeholders’ priorities and performance indicators that can be used to set goals. Take care to note both areas in which the O&M program is succeeding and areas in which the O&M program is deficient. Doing so will assure that the vision and goals account for both the continuation of success and for continuous improvement. In preparation for a detailed assessment and adjustment to maintenance activities, review the Reliability Centered Maintenance Guide (NASA 2000) and the Best Practices Guide (FEMP 2010).

Additional Resources

Though not directly related to O&M, the U.S. Department of Energy’s 50001 Ready program (DOE n.d.) has proven effective in helping facilities manage their energy resources. Similar principles apply in O&M management, and the 50001 Ready Navigator is a starting point to understand the process of establishing a vision and goals.

Definitions

- Computerized Maintenance Management System (CMMS). A computerized system to assist with the effective and efficient management of maintenance activities through the application of computer technology. It generally includes elements such as a computerized work order system, capabilities for scheduling routine maintenance tasks, recording and storing standard jobs, bills of material, applications parts lists and equipment manuals.

- Facility Stakeholders. All individuals and organizations with a vested interest in the facility operation and mission. This includes all building occupants and will likely also include off-site management personnel. In the context of this Best Practice, stakeholders will typically be limited to representatives for all parties involved.

- Predictive Maintenance. An equipment maintenance strategy based on measuring the condition of equipment to assess whether it will fail during some future period, and then taking appropriate action to avoid the consequences of that failure.

- Preventive Maintenance (PM). An equipment maintenance strategy based on replacing, overhauling or remanufacturing an item at a fixed interval, regardless of its condition at the time.

- Proactive Maintenance. The collection of efforts to identify, monitor and control future failure with an emphasis on the understanding and elimination of the cause of failure. Proactive maintenance activities include the development of design specifications to incorporated maintenance lessons learned and to assure future maintainability and supportability, the development of repair specifications to eliminate underlining causes of failure, and performing root cause failure analysis to understand why in-service systems failed.

- Reactive Maintenance. The work required to restore a component to a condition substantially equivalent to its originally intended and designed capacity, efficiency, or capability. Reactive maintenance is also known as corrective maintenance, and a reactive maintenance strategy is also known as run-to-failure. No actions or efforts are taken to maintain the equipment as the designer originally intended to assure design life is reached.

- Reliability Centered Maintenance. The process used to determine the most effective approach to maintenance. It involves identifying actions that, when taken, will reduce the probability of failure and that are the most cost effective. It seeks the optimal mix of condition-based actions, other time- or cycle-based actions, or the run-to-failure approach.

Sources of Information

DOE (n.d.). 50001 Ready Program. U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Advanced Manufacturing, Washington, DC. https://www.energy.gov/eere/amo/50001-ready-program.

Doran, George T. 1981. “There’s a S.M.A.R.T Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives,” Management Review 70(11):35–36. https://community.mis.temple.edu/mis0855002fall2015/files/2015/10/S.M.A.R.T-Way-Management-Review.pdf

FEMP ─ Federal Energy Management Program. 2010. Operations & Maintenance Best Practices: A Guide to Achieving Operational Efficiency. Release 3.0. Prepared by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory for FEMP, Richland, WA. https://www.wbdg.org/FFC/DOE/DOECRIT/femp_omguide.pdf.

GAO ─ General Accounting Office. 1990. NASA Maintenance: Stronger Commitment Needed to Curb Facility Deterioration. GAO Report NSIAD-91-34, U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO), Washington, D.C. https://www.gao.gov/assets/150/149913.pdf

GAO ─ General Accounting Office. 1991. Federal Buildings: Actions Needed to Prevent Further Deterioration and Obsolescence. GAO Report GGD-91-57, U.S. General Accounting Office, Washington, D.C. https://www.gao.gov/assets/160/150491.pdf

GAO – General Accounting Office. 1993. Federal Research: Aging Federal Laboratories Need Repairs and Upgrades. GAO Report RCED-93-203, U.S. General Accounting Office, Washington, D.C. https://www.gao.gov/assets/220/218554.pdf

NASA – National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2000. Reliability Centered maintenance Guide for Facilities and Collateral Equipment. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C. Accessed September 17, 2019 at https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/codej/codejx/Assets/Docs/RCMGuideMar2000.pdf

NRC – National Research Council. 1998. Stewardship of Federal Facilities: A Proactive Strategy for Managing the Nation’s Public Assets. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.17226/6266.

Published December 2020