- Best Practices for Equipment O&M

-

O&M Best Practice Issue Discussions

- Advanced Maintenance Approach: Reliability Centered Maintenance

- Applying Key Performance Indicators

- Comprehensive O&M Program

- Contract Challenges and Improvements

- Cybersecurity for O&M Systems

- Existing Building Commissioning Procurement

- Healthy Building O&M

- Integrating and Analyzing Building Information to Support O&M

- Maintenance Approaches

- OMETA: An Integrated Approach to Operations, Maintenance, Engineering, Training, and Administration

- Prioritizing O&M Actions

- Re-tuning Buildings

- Tools

- Glossary

Cybersecurity for O&M Systems

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Discussion

- Solutions and Actions

- Conclusions and Next Steps

- Additional Resources

- Definitions

- References

Introduction

The purpose of this Best Practice is to highlight cybersecurity best practices for operations and maintenance (O&M) staff. This Best Practice does not address high-level cybersecurity related to information technology (IT) roles, but rather focuses on cybersecurity practices relevant to O&M roles.

The buildings that we live and work in are getting “smarter,” or more connected. New technologies are entering the smart building ecosystem at a rapid pace to help reduce energy consumption, improve comfort, and provide real-time monitoring and control. Unfortunately, this progress and convenience also introduces new opportunities for information to be compromised. The Internet of Things (IoT) is a rapidly evolving collection of diverse technologies that interact with the physical world. It is a system of interrelated computing devices with the ability to transfer data over a network without requiring human-to-human or human-to-computer interaction, which has introduced new possibilities for cybersecurity threats. The consequences of a security breach can be significant, and cyberattacks can severely affect an agency or organization’s ability to execute its mission.

Ensuring that standing procedures or policies are followed regarding cybersecurity for O&M, along with cultivating a climate of awareness, can play a vital role in minimizing cyber risks. The effectiveness of cybersecurity is not maximized when responsibility is left solely to an IT department. Successful cybersecurity is the responsibility of all staff, including O&M staff. A knowledgeable and well-trained staff can serve as the first line of defense against cyberattacks.

Discussion

Relevant History

The historical focus of cybersecurity is IT. Advancing technologies such as connected controls led to linking IT and operational technology (OT) to form interconnected networks. However, while these technologies advance, the cybersecurity that protects these systems lags. Many professionals still consider information more valuable than connected systems, leading to the continued negligence of OT security. Devices that are connected to a network or have an Internet Protocol (IP) address are especially at risk for cyber threats because of these devices’ ability to exchange information. For example, many facilities now use a central building automation system (BAS) to monitor and control heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems and digital devices (thermostats, sensors, motor controls, etc.) across multiple buildings. Without adequate security, these devices and OT systems are vulnerable to cyberattacks. The OT systems are introducing new risk to traditional IT operations, and thus need to be secured.

As a result of cyberattacks on operational systems, businesses and federal agencies are recognizing the importance of security and are mandating that their staff begin taking an active approach to O&M cybersecurity. One concern is that connected devices with weak security may be accessed to reach higher-security devices or information through the network. Security gaps with OT may also be exploited to take equipment hostage or cause damage to the equipment, building, or tenants. For example, in December 2013, over 40 million credit and debit cards were stolen from Target stores using login credentials from a third-party HVAC contractor. The hackers stole the login credentials and used the remote access capability to infiltrate the IT network (The SANS Institute 2014).

Threats related to OT cybersecurity may have dangerous implications, but those threats can be neutralized or avoided using the proper precautions. In addition to software that might be installed by an organization’s IT department, there are regular practices that can be adopted by O&M staff that minimize cybersecurity risks related to OT.

Interested Parties

The key individuals responsible for O&M cybersecurity include but are not limited to facility managers and building O&M technicians, senior management, and occupants. The O&M staff should also communicate with IT staff and keep them well informed. Cybersecurity teams do not work in a vacuum and need feedback and support from end users. As cybersecurity becomes a greater priority for the building sciences industry, facility managers must be able to integrate the resources and practices for effective cybersecurity into current building O&M practices.

Existing Standards and Policy

The Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 includes mandates for agency heads and for the Director of the Office of Management and Budget and the Secretary of Homeland Security. These include the provision of risk management tools and a requirement for agency heads to assure that all agency members act in accordance with established cybersecurity standards. This act can be complied with by increasing cybersecurity awareness and literacy in the workplace.

Agency assets that are considered critical infrastructure should comply with Executive Order (EO) 13800, Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure, which mandates proper risk identification and management from agencies supporting critical infrastructure. Agencies or organizations not housing critical infrastructure can support this EO by training members in OT cybersecurity, identifying potential cybersecurity threats, and developing plans to mitigate risk.

Increasing O&M cybersecurity strengthens an organization’s ability to protect its assets and act in accordance with the EO on America’s Cybersecurity Workforce, EO 13870, which aims to increase cybersecurity training. As threats related to building operation increase in magnitude and frequency, O&M organizations and their staff will benefit from improving their posture toward cybersecurity.

Considerations for O&M

Effective cybersecurity is a conscious effort from all individuals that work with or around networked systems. Computerized maintenance management systems (CMMSs), connected controls, O&M personnel information, advanced and smart meters, and building or equipment access are examples of systems considered for O&M cybersecurity. Cybersecurity should be considered by all O&M staff as they perform their functions. Staff should be knowledgeable about applicable policies and what aspects of cybersecurity, such as clearance of systems involving network connections, should be deferred to the IT staff, as well as those that are about O&M staff responsibilities such as granting access or sharing passwords with contractors.

U.S. Department of Energy Program Interactions

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER) addresses the increased frequency and sophistication of cyberattacks. CESER has partnered with national laboratories and utility companies to develop and test pilot programs that address cybersecurity for OT systems.

FEMP’s Energy and Cybersecurity Integration program provides guidance and direction on how to enhance the cybersecurity posture of federal facilities. The tools and resources that are available can help mitigate cyber threats and meet the requirements set forth in EO 13800. These tools and resources are discussed more in the Additional Resources section below.

Solutions and Actions

O&M staff are responsible for compliance with site and agency cybersecurity requirements. The following are some of the methods to improve cybersecurity posture and protect assets from cyberattacks.

- Identify an O&M Cybersecurity Champion

- Implement proper password management practices

- Restrict remote access to authorized users

- Communicate regularly with O&M and IT staff

- Be aware of possible insider threats and report any abnormal behavior

- Report all possible system abnormalities and/or intrusion attempts to IT staff

- Develop a response and recover plan to recover from a cyberattack.

O&M Cybersecurity Champion

The main defense in O&M cybersecurity is familiarizing staff with and following existing standards and protocol. However, because of day-to-day tasks and other unforeseen issues, not all personnel can stay up to date with cybersecurity topics. Therefore, O&M staff should identify an individual within the team to become a subject matter expert. This individual would be responsible for the following:

- Assess the scope of current cybersecurity standards and be aware of all security procedures.

- Understand how the organization’s cybersecurity criteria applies to O&M activities.

- Attend meetings with IT staff and get periodic training on relevant topics.

- Disseminate information and provide O&M cybersecurity training to the rest of the staff.

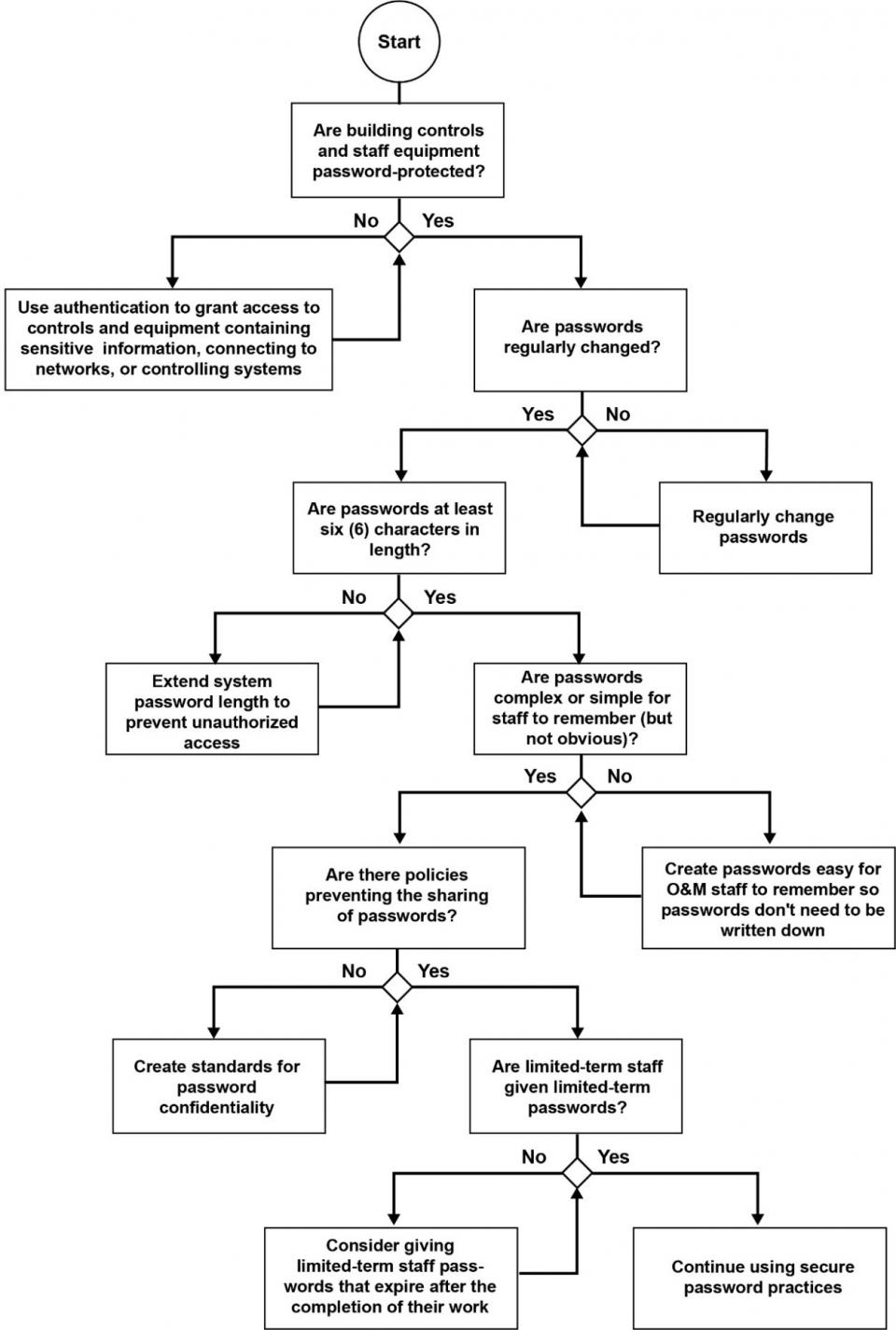

Password Management

Proper password management practices are key to O&M cybersecurity. The following are some of the best practices that should be followed by O&M staff (NIST 2015).

- Refer to agency and site policies for password conduct and contractor access

- Only those who need access to a system should be granted access

- Update passwords for staff and equipment regularly using easily remembered but not obvious password choices:

- Avoid using names, usernames, or birthdates in password selections

- Long and diverse passwords are more secure, but they should also be easy for staff to remember so the passwords do not need to be written down

- The “remember password” feature of web browsers should not be used

- Passwords should not be shared or transmitted in email messages

- Passwords should not be recorded somewhere that could be found by unauthorized personnel

- The passwords of departing staff members should be terminated. Temporary staff such as limited-term contractors should be given temporary passwords that expire when they finish their work.

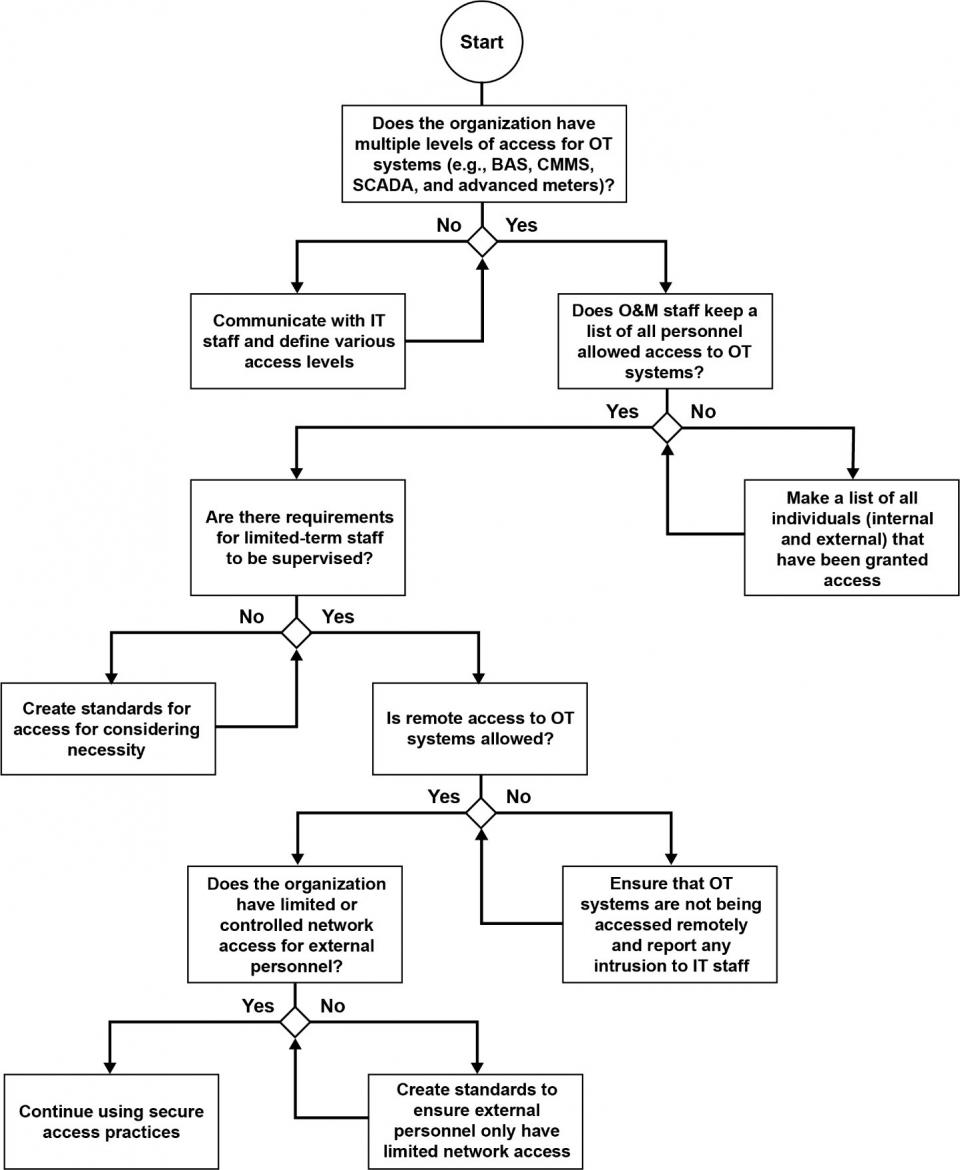

Remote Access

A common weakness in OT systems is ineffectively controlled remote access. In the past, this was not a significant risk because IT and OT systems were isolated and access to OT systems did not pose a significant risk to operations nor did it hamper an agency’s ability to execute its mission. However, system integration can lead to vulnerabilities that can affect mission-critical infrastructure and functions. Properly securing remote access for all users must be part of any cybersecurity strategy. The following are some of the best practices for remote access (DHS 2010; NIST 2015).

- Communicate with IT staff to assure that all systems requiring remote access, such as BAS, CMMS, SCADA, etc., have proper security measures in place.

- Assure that remote access is only available to authorized users and provides an appropriate level of access (e.g., view, write, admin, etc.).

- Make a list of all individuals that have been provided remote access.

- External stakeholders, such as vendors or contractors, typically require remote access to provide system maintenance and support. O&M staff should work with their IT department to assure that proper access control is in place.

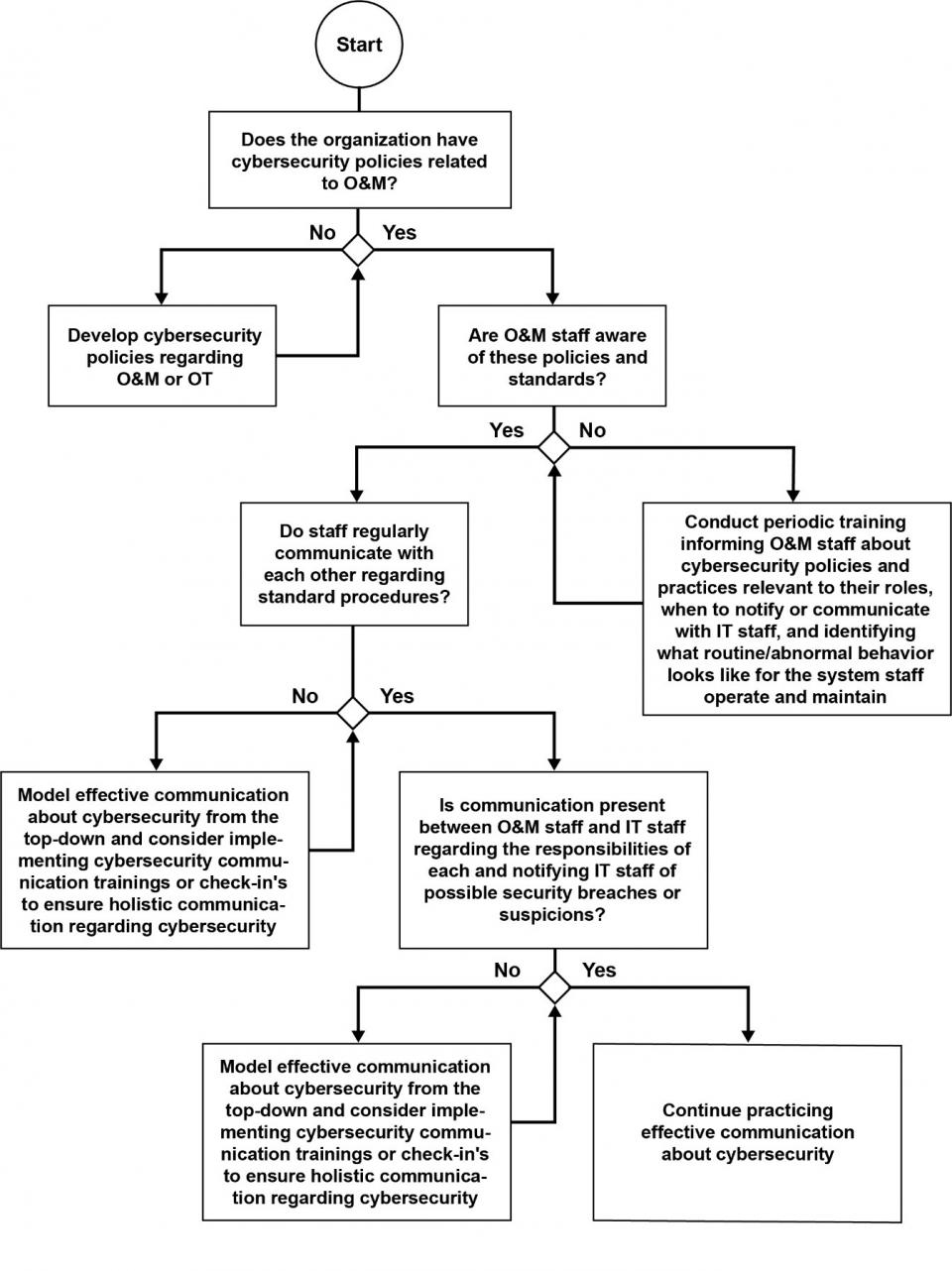

Communication

Another key measure for maintaining strong cybersecurity is communication. O&M staff should regularly communicate with each other and IT staff about cybersecurity practices and any feasible signs or risks of a security breach. If a possible symptom of a cybersecurity threat is detected or even suspected, O&M staff should notify the IT department. Encouraging a culture of cybersecurity awareness among O&M staff can help prevent staff negligence or oversight if actual threats are presented.

Insider Threat (Abnormal Staff Behavior)

An insider threat is one of the most critical threats to an organization. Sabotage, theft, espionage, fraud, and competitive advantage can be carried out by abusing authorized access and mishandling physical devices. According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), some behavioral indicators of malicious threat activity include:

- Remotely accessing the network while sick or on vacation

- Working odd hours without proper authorization

- Interest in matters outside of duty scope

- Signs of vulnerabilities, such as drug or alcohol abuse, financial difficulties, or hostile behavior.

Creating a positive work environment, providing continual training, improving security tools, and enhancing awareness of unintentional insider threats are some of the ways to combat insider threats. Both the DHS and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) offer training courses to assist agencies and organizations in preparing for and mitigating insider threats.

Intrusion (Abnormal System Behavior)

To detect abnormalities, O&M staff should discuss and identify routine operating behavior. This might differ depending on the system or equipment and its specific functions. Not every mishap indicates a cybersecurity threat, but staff should be aware of the possibility of threats and should keep track of mishaps to identify possible intrusion efforts or repeat behavior. The O&M Cybersecurity Champion should work with all staff members and communicate with the IT staff to assure that all abnormal behaviors get reported. The best way to prevent intrusion is to follow the direction of the IT staff and keep antivirus and other intrusion detection programs up to date.

Protect and Detect

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) lists possible cyber threat symptoms for industrial control systems (ICS), which could also apply to other connected systems as follows (NIST 2015, pages 6–25 and 6–26):

- Unusually heavy network traffic

- Out of disk space or significantly reduced free disk space

- Unusually high central processing unit usage

- Creation of new user accounts

- Attempted or actual use of administrator-level accounts

- Locked-out accounts

- Account in use when the user is not at work

- Cleared log files

- Full log files with an unusually large number of events

- Antivirus or Intrusion Detection System alerts

- Disabled antivirus software and other security controls

- Unexpected patch changes

- Machines connecting to outside IP addresses

- Requests for information about the system (social engineering attempts)

- Unexpected changes in configuration settings

- Unexpected system shutdown.

Response and Recovery Plan

Finally, O&M staff should make sure that they have a plan in place to recover from a cyberattack. While having a robust cybersecurity policy that focuses on prevention is key to limiting the impact on an agency, having a response and recovery plan is just as important. A standardized response plan should address possible threats and their outcomes as well as procedures to respond to each scenario. The goal for response and recovery in the event of a cyberattack is to contain the issue and repair systems back to the status quo. Development of a response and recovery plan should include the following:

- Any incident should be reported to the IT department for further support. Follow site guidelines for incident assessments and recovery actions after an event.

- Develop a communications plan to keep all staff informed.

- Perform a business impact analysis in the event of a cyberattack. Plan should include best practices and methods for how to provide business continuity.

- Specific roles should be considered in the plan so that staff members know how to proceed in the event of an attack. However, the actions must not be restricted to one individual and should be executed by all capable staff members.

- Plans should involve the protection of critical equipment and systems.

- Staff may be given a specialized password that alerts IT or other staff of duress. While O&M staff action is vital in the event of cyberattacks, containing these issues is the responsibility of IT staff.

- Preventive measures to aide response and recovery include setting up systems to fail to a safe state, assuring automatic starting measures for backup devices, installing alarms or alerts for system failures, setting up systems with the ability to be isolated, and conducting incident response training.

- The plan should always be updated after an incident with lessons learned from the cyberattack.

Other practices for good cybersecurity:

- Physical

- If applicable for site or agency policy, assure that contractors or limited-term staff are always accompanied by a staff member.

- Assure that only approved devices or software are installed.

- Install locks to prevent access to certain systems or areas of the facility.

- Technical

- Keep antivirus software updated

- Beware of phishing and spear phishing emails

- Limit USB usage when possible and check USBs with IT before using

- Enable auto-sign-off features on technology after a designated time

- Consider applying a multi-step authentication to critical systems

- Use a virtual private network (VPN) when using devices on a public or questionable network.

- Administrative

Conclusion and Next Steps

Anticipating and reacting to every potential cyber threat is neither an efficient nor a sustainable strategy because of the large resource and manpower requirements. Identifying critical systems and guaranteeing staff compliance with cybersecurity protocol helps to narrow the focus and costs of security. One of the most critical steps in preventing a cyberattack is having well-trained and informed staff. Periodic trainings and evaluations may increase awareness and proactivity toward cybersecurity. O&M staff and IT staff should communicate often to assure the overall effectiveness of O&M cybersecurity systems. Staff should also use secure password and remote access practices to minimize the likelihood of a device or system security breach.

Cybersecurity threats wear a variety of masks, but they are mostly indicated by abnormalities (insider threat and system intrusion). O&M staff should define normal and abnormal behavior so that systems can aide in the identification of a possible breach. Not every abnormal system behavior indicates a breach, so the best response is to investigate occurrences and notify IT of behavioral variants. Systems may also be prepared by staff to aide in threat response, such as being set up to fail in a safe way and record or alert to failed or allowed attempts that try to access a system. O&M staff should be informed and prepared to act in the case of an attack. If an attack does occur, a risk assessment should follow to discern the proper response and recovery avenue.

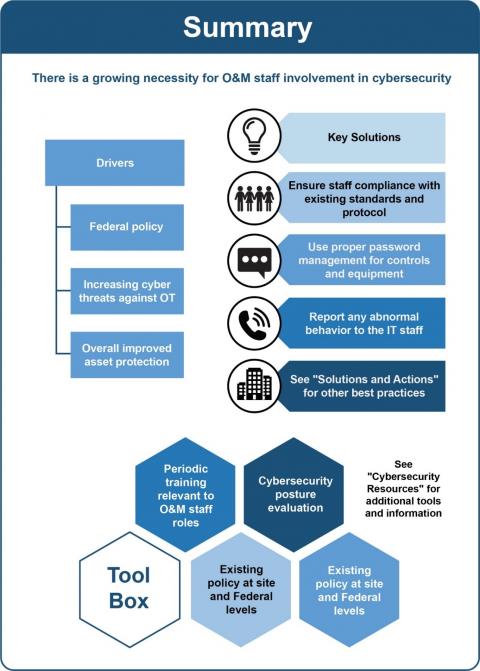

A summary of cybersecurity recommendations is provided in Figure 1. Figure 2 through Figure 4 provide decision trees that contain a high-level overview of cybersecurity best practices. These flow charts are intended to assist O&M staff in their day-to-day operations. To learn more about a site’s cybersecurity posture and mitigate risks, O&M staff should work with their IT staff and utilize the Facility Cybersecurity Framework (FCF) tool to conduct a detailed assessment. See Additional Resources for more information.

Additional Resources

Facility Cybersecurity Framework

FCF is an assessment tool that allows facility operators to evaluate, as well as train individuals in, current cybersecurity practices to strengthen overall cybersecurity fluency. Developed by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory for FEMP, FCF includes a core assessment, qualitative risk assessment, comparative evaluation, and a scenario-based training game. Using this tool, agencies and organizations can develop a five-step plan for cybersecurity—identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover. IT departments typically have these policies in place, but O&M staff can use the concept to develop a standardized plan for site assets. The tool can be accessed at https://facilitycyber.labworks.org/fcf/about.

Guide to ICS Security

This publication provides an overview of ICS and further suggestions related to cybersecurity. These systems include SCADA, DCS, and PLC, among other control systems. Discussion is included regarding the development of ICS-specific policy and the implementation and management of ICS security. This paper addresses common threats to ICS and prescriptive security objectives to prevent and defend against threats. This paper is intended for anyone working with or alongside ICS. The publication can be accessed at https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-82r2.pdf (NIST, 2019)

NIST Cybersecurity Framework Version 1.1

The NIST created this framework to comply with the Cybersecurity Enhancement Act of 2014. This framework intends to bolster cybersecurity for critical infrastructure, but it is also applicable to any organization that utilizes connected devices. The framework is broad and adaptable to an organization’s specific cyber risks. Components of the framework are the framework core, framework implementation tiers, and a framework profile. The framework can be accessed at https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework/framework (NIST, 2019).

Introduction to Buildings Cybersecurity Framework (BCF)

This paper presents an introduction to the BCF, which is based on the principles of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework. It provides an organization with a set of cybersecurity best practices, policies, and procedures. The framework can be accessed at https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=8285228 (IEEE, 2019).

Cybersecurity for Lighting Systems

This paper focuses on network-connected lighting systems (both wired and wireless) and their correlated cybersecurity risks. Explanations of different levels of connected lighting are included along with the degree of cyber threat posed at each level. This paper also describes various types of potential cyberattacks associated with lighting systems. Current testing programs for connected lighting are also described. This paper can be accessed at https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2018/06/f52/cyber_security_lighting.pdf.

Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC) 4-010-06: Cybersecurity of Facility-Related Control System

UFC documents apply to the DoD and provide standards and specifications for the design, construction, modernization, and sustainment of all facilities. UFC 4-010-06 describes requirements for incorporating cybersecurity into the design of all BASs. The criteria can be accessed at https://www.wbdg.org/ffc/dod/unified-facilities-criteria-ufc/ufc-4-010-06.

Definitions

The following are accepted terminology used in cybersecurity for operations and maintenance, as defined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers and Studies.

- Access Control. The process of granting or denying connectivity to system resources. Security safeguards allow different types of access to authorized individuals (e.g., read, write, administrative, etc.).

- Authentication. The ability to verify the identity of a user or device before allowing access to an information system.

- Building Automation System (BAS). A system of digital controllers, communication architecture, and user interface that monitors and controls a building’s mechanical and electrical equipment such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning, lighting, fire protection, vertical transport systems, and irrigation systems. The system can be used to optimize facility operation and reduce energy consumption. Also known as: building control system or energy management system.

- Connected Lighting Systems. A lighting system that is connected to a network for the transmission of data and the control of devices.

- Critical Infrastructure. Systems and assets so vital to an organization that the incapacity or destruction of such may have a debilitating impact on security, economy, public health or safety, environment, or any combination of these matters.

- Cybersecurity. The activity or process of protecting electronic information and communication systems from unauthorized use, modification, or exploitation.

- Cybersecurity Framework. A risk-based approach to managing cybersecurity risk. Typically developed for an entire organization, individual buildings, or critical assets.

- Distributed Control System (DCS). Part of a control system; refers to control achieved by intelligence that is distributed through the process to be controlled, rather than through a centrally located single unit. A DCS includes both software and hardware components.

- Enterprise Building Control System (EBCS). The ability to connect the BAS to the information technology network to provide enterprise-wide online monitoring and control of the building (or multiple facilities) from a web-connected device on the network.

- Industrial Control System (ICS). An information system used to control industrial processes such as manufacturing, product handling, production, and distribution or to control infrastructure assets.

- Information Technology (IT). Any equipment or interconnected system or subsystem of equipment that transmits, receives, processes, stores, or interchanges data or information electronically. IT includes computers, software, firmware, networks, services (including support services), and related resources.

- Insider Threat. The threat that an entity will use his/her authorized access, wittingly or unwittingly, to do harm to the security of an organization.

- Internet of Things (IoT). The interconnection via a network of computing devices embedded in everyday objects, enabling them to send and receive data.

- Intrusion. A set of actions that constitutes a security incident in which an intruder gains or attempts to gain access to a system or resource without having authorization to do so.

- Operations and Maintenance (O&M). Decisions and actions regarding the control and upkeep of property and equipment.

- Operational Technology (OT). The hardware and software dedicated to detecting or causing changes in physical processes through direct monitoring and/or control of physical devices.

- Phishing. Tricking individuals into disclosing sensitive personal information by claiming to be a trustworthy entity in an electronic communication.

- Principle of Least Privilege. The idea that a person should be authorized with the minimum level of access necessary to complete their work.

- Programmable Logic Controller (PLC). A solid-state control system that has a user-programmable memory for storing instructions for the purpose of implementing specific functions.

- Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA). A computerized system that can gather and process data and apply operational controls to geographically dispersed assets.

References

82 FR 22391. May 11, 2017. “Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure.” Federal Register, Executive Office of the President. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/05/16/2017-10004/strengthening-the-cybersecurity-of-federal-networks-and-critical-infrastructure

84 FR 20523. May 9, 2019. “America’s Cybersecurity Workforce.” Federal Register, Executive Office of the President. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/05/09/2019-09750/americas-cybersecurity-workforce

DOE – U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response. Washington, D.C. Accessed July 10, 2019 at https://www.energy.gov/ceser/office-cybersecurity-energy-security-and-emergency-response

FEMP – Federal Energy Management Program. 2018. Cyber Security for Lighting Systems. Accessed June 28, 2019 at https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2018/06/f52/cyber_security_lighting.pdf.

FEMP ─ Federal Energy Management Program. Energy and Cybersecurity Integration. Washington, D.C. Accessed July 10, 2019 at https://www.energy.gov/eere/femp/energy-and-cybersecurity-integration.

DHS – U.S. Department of Homeland Security. 2010. Configuring and Managing Remote Access for Industrial Control Systems. Prepared by the Center for the Protection of National Infrastructure for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, London, U.K. https://us-cert.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/recommended_practices/RP_Managing_Remote_Access_S508NC.pdf

DHS – U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Insider Threat – Training and Awareness. https://www.dhs.gov/cisa/training-awareness.

IEEE – Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. An Introduction to Buildings Cybersecurity Framework. Prepared by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Accessed September 5, 2019 at https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=8285228

NARA ─ The National Archives and Records Administration. FAQ’s About Executive Orders. Accessed August 21, 2019 at https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/executive-orders/about.html.

NICCS ─ National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers and Studies. 2018. Explore Terms: A Glossary of Common Cybersecurity Terminology. Accessed June 28, 2019 at https://niccs.us-cert.gov/about-niccs/glossary#.

NIST ─ National Institute of Standards and Technology. Glossary. Accessed June 28, 2019 at https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary.

NIST ─ National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2015. Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security. NIST Special Publication 800-82 Revision 2, Gaithersburg, MD. Accessed June 24, 2019 at https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-82r2.pdf.

NIST ─ National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2018. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity. Version 1.1, Gaithersburg, MD. Accessed June 28, 2019 at https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework/framework.

PNNL ─ Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Facility Cybersecurity Framework (FCF). Accessed June 24, 2019 at https://facilitycyber.labworks.org/fcf/about.

Security Awareness Hub – Select eLearning awareness courses for DoD and Industry. Insider Threat Awareness. https://securityawareness.usalearning.gov/itawareness/index.htm.

S.2521. 2014. Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014. Public Law 113-283. UFC 4-010-06. Cybersecurity of Facility-Related Control Systems. Department of Defense, Washington, D.C. https://www.wbdg.org/FFC/DOD/UFC/ufc_4_010_06_2016_c1.pdf

The SANS Institute. 2014. Case Study: Critical Controls that Could Have Prevented Target Breach. Accessed August 21, 2019 at https://www.sans.org/reading-room/whitepapers/casestudies/case-study-critical-controls-prevented-target-breach-35412

Actions and activities recommended in this Best Practice should only be attempted by trained and certified personnel. If such personnel are not available, the actions recommended here should not be initiated.

Published April 2021