- Best Practices for Equipment O&M

-

O&M Best Practice Issue Discussions

- Advanced Maintenance Approach: Reliability Centered Maintenance

- Applying Key Performance Indicators

- Comprehensive O&M Program

- Contract Challenges and Improvements

- Cybersecurity for O&M Systems

- Existing Building Commissioning Procurement

- Healthy Building O&M

- Integrating and Analyzing Building Information to Support O&M

- Maintenance Approaches

- OMETA: An Integrated Approach to Operations, Maintenance, Engineering, Training, and Administration

- Prioritizing O&M Actions

- Re-tuning Buildings

- Tools

- Glossary

O&M Contract Challenges and Improvements

Table of Contents

- Introduction/Objective

- Discussion

- Current Status of O&M Contracting

- Best Practices: Operations

- Summary and Future Plans

- Resources and Defined Terms

- Appendices

- References

I. Introduction/Objective

The federal government is the nation’s largest energy consumer (EERE n.d.(a)), and effective operations and maintenance (O&M) in federal facilities is a cost-effective way to assure reliability, safety, and energy and water efficiency. The purpose of this Best Practice discussion is to research and evaluate the current O&M contracting practices as applied to federal facilities to identify improvement opportunities. The research reviewed federal government O&M contracting types, trends, and best practices. Additionally, some innovative contracting practices from the General Services Administration were evaluated in greater detail for their potential impacts across all federal agencies.

The evaluation was intended to determine what practices are being successfully employed in current contracts and/or execution of current contracts, leading to an understanding of what improvements are needed.

O&M contracting continues to be a pillar of facility management in government and private-sector buildings alike. In many cases, contracted (or outsourced) O&M frees facility managers to focus on more core, mission-related requirements while handing off routine activities to experienced contractors. This hand-off often comes in the form of multi-year O&M contracts aimed at keeping facilities operating in a safe, healthy, and efficient manner.

This Best Practice discussion was developed for the Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP) and is intended to assist the federal facility/energy manager as well as contracting staff in charge of contract development, oversight, and valuation.

II. Discussion

The objectives of this discussion are as follows:

- Current status of O&M contracting (Section III)

- Present the trends and drivers in O&M contracting (Sections A and B)

- Introduce the most common types of O&M service contracts and the benefits and challenges of each (Section C)

- Highlight the typical O&M contract award types and the benefits and challenges of each (Section D)

- Introduce key components in O&M service contract development (Section E)

- Best practices in operations (Section IV)

- Innovative O&M contract models (Section A)

- Management best practices (Section B)

- Data collection, tracking, and metrics (Section C)

- Summary and future plans (Section V)

- Summary (Section A)

- Future plans (Section B)

- Resources and defined terms (Section VI)

- Resources (Section A)

- Terms (Section B)

- Appendices (VII)

- Appendix A: Service Contract Types

- Appendix B: Contract Award Types

- Appendix C: Model Comparison.

The summary and next steps (Section IV) offer ideas and concepts for initiating improvements to existing or future O&M service contracts.

III. Current Status of O&M Contracting

A. Trends in O&M

As buildings and building systems become more complex, there is a defined need for experience and expertise beyond the core capabilities of typical O&M program staff. As this need becomes more acute, there has been an uptick in the need for contracted (also called outsourced) O&M services. Other factors contributing to the trend toward contracted O&M services include:

- Recent trends in “smart” and/or “connected” buildings where systems can be monitored, controlled, and diagnosed remotely through contract service providers.

- Facility O&M budgets that have been subject to cost-cutting, and the potential for workforce reductions.

- The accelerated retirement trend due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and with this a potential loss of corporate knowledge resulting in a less-skilled workforce to fill these roles, at least in the near term.

- Vendor-specific O&M requirements to maintain equipment warranties.

- Government regulations that encourage and/or require performance-based contracted services that are affording efficiencies to federal agencies attempting to stay in compliance with an ever-increasing host of requirements, i.e., contracted expertise has higher value in meeting increasingly complicated requirements. There are indicators that performance-based maintenance contracting of these services has reduced both direct and indirect O&M costs (OMB 1998).

- The push to install new technologies such as wind turbines, ground source heat pumps, battery energy storage systems, and solar photovoltaics.

B. Drivers Affecting O&M

The federal sector is experiencing an influx of new drivers that affect O&M. These drivers aim to improve resilience and conserve energy and water while maintaining good stewardship of the land and facilities for the betterment of all. Some of the drivers require performance contracting and recommend obtaining third-party financing opportunities, including energy savings performance contracts (ESPCs) and utility energy service contracts (UESCs), to facilitate implementation. In addition, there are new drivers on metering, climate change, cybersecurity, and emission reduction.

These drivers include the following:

- 42 U.S.C. 8287 authorizes agencies to enter contracts. The Department of Energy (DOE) Rule at 10 CFR 436 subpart B outlines methods and procedures for energy savings performance contracting and includes participation in utility programs to increase energy efficiency, conserve water, and/or manage electricity demand.

- The Federal Acquisition and Streamlining Act (FASA) of 1994 (Public Law 103-355) was introduced to simplify government procurement of goods and services. This act changed the government procurement strategy from lowest bid to best value, enabling tradeoffs between price and technical merit.

- The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR subpart 23.2) states that agencies should maximize use of the authority provided in the National Energy Conservation Policy Act (42 U.S.C. 8287) to use an ESPC, when life-cycle cost-effective, to reduce energy use and cost in the agency’s facilities and operations. Further, agencies must use the procedures, selection method, and terms and conditions provided in 10 CFR Part 436, subpart B.

- 42 U.S.C. 8253 requires agencies to use performance contracting to implement at least 50% of life-cycle cost-effective projects (e.g., identified/reported conservation measures) within the first 2 years after the evaluation is completed.

The latter requirement will encourage more agencies to determine how to execute a performance contract, such as an ESPC or UESC. A UESC is a limited-source contract between a federal agency and a serving utility for energy management services. While an ESPC is a financial mechanism used to pay for energy savings, it constitutes a partnership between a facility owner and an energy service company (ESCO) and is considered a time- and cost‐effective method for completing comprehensive energy upgrades (EERE 2011). These ESPC/UESC models set a precedent for other performance contracting and third-party financing.

O&M is critical to the success of any project (ESPC/UESC included), and there are pros and cons to who performs the O&M. The ESPC guidance suggests that ideally the ESCO should perform the operation and all maintenance activities (Federal ESPC Steering Committee 2013). However, the O&M can be assigned to an ESCO or to the agency or shared between the ESCO and the agency. The ESCO is typically responsible for providing O&M training. The FEMP UESC guidance suggests that the utility is required to provide the O&M training in the more common instance where the agency continues to operate and maintain the installed equipment (EERE n.d.(b)).

The following situations influence and/or dictate whether the agency or the utility contractor performs the O&M and repair and replacement (R&R):

- The agency is accustomed to performing the duties and cannot reallocate responsibilities.

- Access is limited and requires a government entity to perform the O&M.

- The new technologies are outside of an O&M staff’s core capabilities, and training per the Federal Buildings Personnel Training Act of 2010 (Public Law 111-308) is cost prohibitive.

- Warranty terms stipulate who performs the O&M and/or the R&R.

Regardless of who performs the O&M/R&R, the requirements and roles must be clearly defined and, if not performed per the outlined requirements, the tasks can be reassigned.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 (Public Law 109-58) established initial guidelines for metering of federal facilities. Metering and sub-metering of energy and water is a critical component of a comprehensive O&M program. 42 U.S.C. 8253 requires that federal agencies establish guidelines to support metering, and “each agency shall use, to the maximum extent practicable, advanced meters or advanced metering devices that provide data at least daily and that measure at least hourly consumption of electricity and water in the federal buildings of the agency.” The Federal Building Metering Guidance (per 42 U.S.C. 8253(e), Metering of energy use), updated November 2014, replaces the February 2006 guidance. The Energy Act of 2020 inserted “water” into the requirements in several places to advance potable water conservation and metering (EERE n.d.(c)). Agencies were required to implement energy and water metering in all federal buildings by October 1, 2022 (42 U.S.C. 8253).

Meters provide data that can inform building operators and maintenance staff and can be used to:

- Reduce energy and water use

- Reduce energy and water costs

- Improve overall building operations

- Facilitate safe operations

- Improve or help troubleshoot equipment operations.

The four predominant levels of resource metering are (EERE 2010):

- One-time/spot measurements

- Run-time measurements

- Short-term measurements/monitoring

- Long-term measurements/monitoring.

Each level has unique characteristics because no one monitoring approach is useful for all projects. However, an advanced level of metering is required to perform continuous monitoring and commissioning and advanced fault detection and diagnostics (FDD). FDD is the process of identifying (detecting) deviations from normal or expected operation (faults) and diagnosing the problem and/or its location. FDD can be used to diagnose anomalies in the performance of critical equipment such as boilers, chillers, motors, pumps, and exhaust fans. More recent advancements in FDD have enabled software, which can be integrated with the building automation system (BAS), to translate anomalies into real-world faults and deliver notifications to operators detailing not only the root cause of an issue, but how to resolve the problem.

Executive Order (EO) 14057, Catalyzing America’s Clean Energy Economy Through Federal Sustainability, set provisions to replace fossil-fueled equipment with carbon-pollution-free electricity by 2030, striving for a net-zero emissions building portfolio by 2045. Further, the EO requires net-zero emissions from overall federal operations by 2050, including a 65% emissions reduction by 2030. There are five commitments that form the pillars of the EO, but the following three are expected to affect O&M more directly:

- Achieve climate-resilient infrastructure and operations.

- Build a climate- and sustainability-focused workforce.

- Prioritize the purchase of sustainable products.

The EO has prompted agencies to lead by example and adopt a net-zero emissions target. These agencies are planning to abate climate risk by phasing out greenhouse gas sources, such as gas and other fossil fuels, increase efficiency of their buildings and equipment, and optimize how and when electricity is used. In many cases, new technologies (e.g., heat pump water heaters) will be evaluated and introduced into the asset list, along with innovative approaches such as partnering with industry and communities. In addition, when federal buildings are being modernized using performance contracting as available, the renovations shall increase water and energy efficiency, reduce waste, electrify systems, and promote sustainable locations for federal facilities to strengthen the vitality and livability of the communities in which federal facilities are located.

Agencies will need to be more proactive, adaptive, and resilient. The reactive strategies of the past should transition to proactive and predictive strategies. Agencies are faced with planning O&M in an uncertain future to meet stretch goals that can provide resilience against the short- and long-term effects of climate change. They can no longer react to an emergency and/or natural disaster; rather, they will have to evaluate risks and probabilities and make operational capability improvements to eliminate, mitigate, and/or recover quickly from impacts to key missions.

The Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (Public Law 113-283) includes mandates to provide risk management tools, establishing and implementing cybersecurity standards, as well as increasing cybersecurity awareness and literacy in the workplace. For critical facilities and infrastructure, agencies need to comply with EO 13800, Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure, to improve the nation’s cyber posture and capabilities in the face of intensifying cybersecurity threats. The focus is on modernizing federal information technology infrastructure and working with state and local governments and/or private-sector partners to secure critical infrastructure.

Historically, cybersecurity (the practice of protecting critical systems and sensitive information from digital attacks) was considered an information technology issue. However, cybersecurity is currently considered the entire agency’s responsibility. Cybersecurity measures need to be designed and implemented to combat threats against networked systems and applications, whether those threats originate from inside or outside of an agency.

O&M program staff should implement procedures or policies regarding cybersecurity and cultivate a climate of awareness. O&M programs often include networked computerized maintenance management systems (CMMSs), BASs, advanced controls, advanced and smart meters, and more. These systems need to be protected. Successful cybersecurity is the responsibility of all staff, including O&M staff. A knowledgeable and well-trained staff can serve as the first line of defense against cyberattacks. However, the security system complexity, created by disparate technologies and a lack of in-house expertise, can require outsourcing these service needs.

There are many drivers and trends that affect O&M, such as the FASA rule (Public Law 103-355) that simplified government procurement to allow for best value rather than low bidder—other examples are those requiring performance contracting. These are challenging the normal process of O&M contracting.

C. Service Contract Types

Historically, there have been four fundamental types of O&M service contracts: full coverage, full labor, preventive maintenance, and inspection contracts (PECI 1997), and variations thereof. These four contract types are still used and can address entire facilities, facility systems, or individual pieces of equipment. Beyond the existing diversity, any given site, depending on its size and complexity, may use multiple contract types to satisfy their O&M needs.

The introduction of new procedures, technologies, and contract vehicles has changed the O&M service industry, and this evolution is expected to continue. The four main contract types are listed in Table 1 with their associated benefits and challenges. A more detailed description of each is provided in Appendix A.

Table 1. Service Contract Types

Contract Type | Benefits | Challenges |

Full coverage |

|

|

Full labor |

|

|

Preventative |

|

|

Inspection |

|

|

D. Contract Award Types

A wide selection of contract award types is available to the government and contractors in order to provide needed flexibility in acquiring the large variety and volume of supplies and services required by agencies (FAR part 16). Contract award types vary according to the following:

- The degree and timing of the responsibility and risk assumed by the contractor for the costs of performance.

- The amount and nature of the profit incentive offered to the contractor for achieving or exceeding specified standards or goals.

The award types are grouped into two broad categories—fixed-price contracts and cost-reimbursement contracts. The specific contract types range from firm-fixed-price, in which the contractor has full responsibility for the performance costs and resulting profit (or loss), to cost-plus-fixed-fee, in which the contractor has minimal responsibility for the performance costs and the negotiated fee (profit) is fixed. In between are the various incentive contracts in which the contractor’s responsibility for the performance costs and the profit or fee incentives offered are tailored to the uncertainties involved in contract performance. Details of the four main options are provided in Appendix B.

As mentioned, contract variations have evolved. A performance-based/end-result contract is a relatively new concept that focuses on a result rather than the process. Over the past decade, the Office of Federal Procurement Policy initiated a performance-based service contracting (PBSC) pledge program (OMB 1998) to encourage federal agencies to use this form of contracting. PBSC recommended the use of a fixed-price contract with incentives to encourage optimal performance.

Some of the tasks associated with performance-based contracting differ from traditional contracting and may include the following:

- Develop with a manageable facility, system, or piece of equipment.

- Describe the work to be completed in terms of the required results rather than how the work is to be done, with what tools and materials, and over what duration/number of hours.

- Consider evaluation aspects of delivering performance versus a set of completed actions.

- Engage contractor in partnership for optimized maintenance, reducing unnecessary activities but affecting reliability, efficiency, and cost.

- Build in cost and tracking from the outset to evaluate pilot performance.

- Evaluate, report, and improve.

Likewise, with incentives-based contracting, some of the variations differ from traditional contracting and may include the following:

- Initiate with a manageable facility, system, or piece of equipment.

- Develop evaluation metrics based on action or improvement.

- Develop incentive amounts (e.g., shared savings percent of cost/energy savings).

- Engage contractor to participate in partnership of enhanced maintenance by improving operations to affect reliability, efficiency, and cost.

- Build in cost and tracking from the outset to evaluate pilot performance.

- Evaluate, report, and improve.

Another variation is the indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity (IDIQ) contract. The IDIQ contract is typically awarded as a cost reimbursement or firm fixed price with a “partner” contractor. The contract obtains supplies or services but does not specify a firm quantity that will be issued and delivered during the period of the contract (as delivery orders or task orders). The IDIQ contract is used when the government cannot predetermine, above a specified minimum, the precise quantities of supplies or services they will require during the contract period and thus can only commit to a minimum quantity.

E. O&M Contract Components

Not all O&M contracts are required to have the same content and/or components. However, most contracts will have some form of the following elements: scope, objectives, and priorities. Within each of these elements lie opportunities for the building owner/manager to best delineate needs and expectations.

- Scope: The scope should reflect the owner’s expectations and include all contract elements comprising management, supervision, labor, equipment, and supplies. Also included are the required actions for efficient and effective operation, scheduled/unscheduled maintenance, repair, and replacement (as needed) for all covered equipment and systems.

- Objectives: The objectives will often include the actions and activities associated with desired outcomes (PECI 1997), for example:

- Provide maximum occupant comfort.

- Conduct effective inspections and surveillance to avoid emergency breakdowns.

- Apply preventive, predictive, and reliability-centered maintenance procedures to minimize premature equipment failure.

- Improve energy, water, and resource efficiency of all covered equipment and systems.

If actions/activities spell out the process as well, it is considered a more prescriptive contract as opposed to a performance-based contract, which will focus on the outcomes.

- Priorities: It is very important to delineate the priorities at the outset of the contract, especially if using a very comprehensive prescriptive type of contract. Given the size, complexity, and thoroughness of traditional O&M contracts, some form of owner priorities will help the contractor determine where to (and how to best) spend available time. These priorities may take the form of ranked equipment schedules or a list of weighted contract objectives. The key to a successful contract is specific and clear identification of the owner’s priorities.

IV. Best Practices: Operations

A. Innovative O&M Contract Models

The operations aspect of any O&M program should encompass actions required to keep all systems and equipment operating efficiently. Transferring these requirements to the O&M contract is a necessity.

For all service and award type contracts and fee structures, best-in-class O&M programs (in-house or outsourced) are finding great value in emphasizing the operations aspect of a program. Simply repairing and replacing parts and/or equipment is not enough. The operations aspect focuses on how equipment and systems function autonomously but are integrated with connected systems and the building. Many of the recommended operational efficiency activities fall under the well-known basic principles of efficient building recommissioning or building re-tuning™, such as turn it off, turn it down, mitigate simultaneous heating and cooling, and reduce infiltration and outdoor air (PNNL 2021a).

When outsourcing the O&M tasks, the most effective O&M contracts are built off relationships (or partnerships) between the owner and the contractor. These partnerships focus on a clear understanding of the contract components—scope, objectives, and priorities. The team approach builds trust and usually result in actions and activities that involve personnel from both parties focusing on operational effectiveness and efficiency.

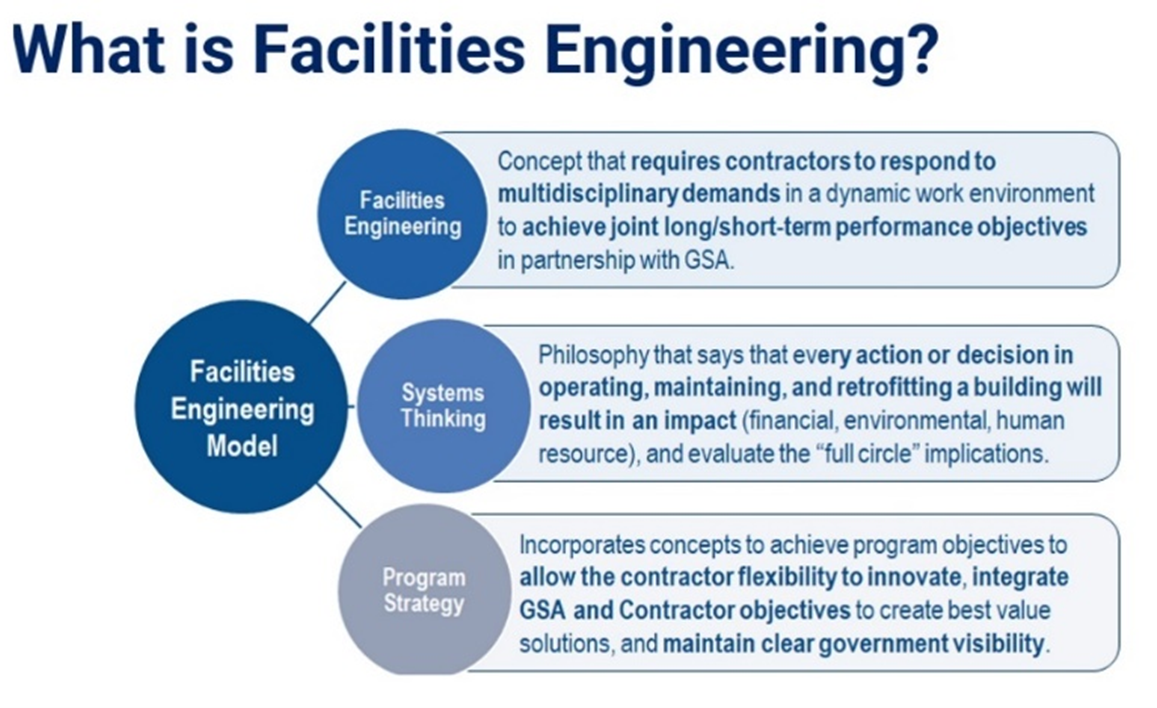

One federal agency has piloted the partnering philosophy for over 15 years, with some success. Their model is termed facilities engineering and applies a systems thinking methodology that is incorporated into a performance-based contract (Figure 1).

Systems thinking is, literally, a system of thinking about systems (Forbes 2020). It involves taking a holistic evaluation of agency and interrelationships within or outside organizations to achieve successful collaborations. This model uses systems thinking to focus on making a best-value-based contractor selection and then allowing and expecting the contractor to bring their expertise in all elements of the O&M contract. Ultimately, the desired outcome has the contractor executing traditional contract elements as well as nontraditional contract elements, including:

- Technical, managerial, and decision-making elements

- Project management and evaluation

- Asset management and modernization.

These additional elements can be layered on top of typical (or enhanced) requirements of energy and water conservation, sustainability stewardship, and short- and long-term planning.

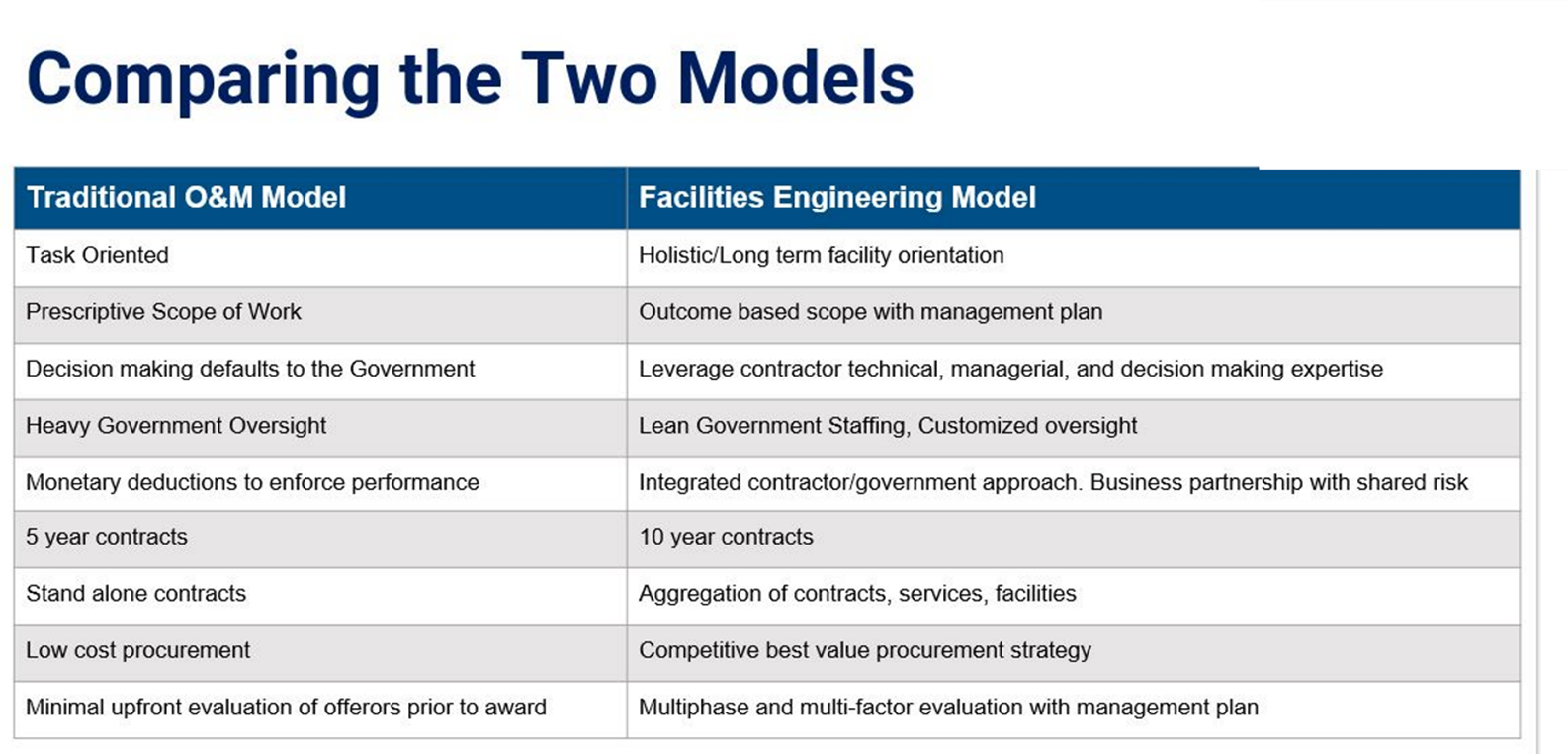

Further, the model has shown that a paradigm shift is required to achieve the “best value” for the government, resulting in significant differences between the traditional O&M contract model and the facilities engineering model (Appendix C). However, this takes time and effort by all stakeholders involved.

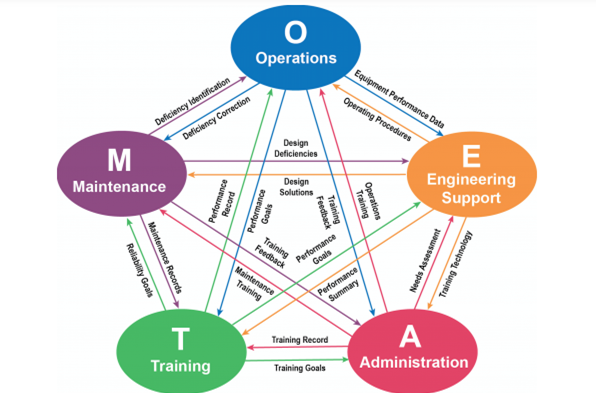

Another concept that follows the systems thinking approach is the OMETA concept (PNNL 2021b). OMETA stands for Operations, Maintenance, Engineering, Training, and Administration. It is a model that considers all elements of supporting infrastructure as integral parts of the larger system. From an O&M perspective, the five functional areas (shown in Figure 2) interact with the other groups and together make up a holistic approach to O&M.

Each functional area has its own activities and relationships with the other groups. By looking at the whole system, including how functional areas interact, the opportunities for improvement may be revealed, such as a functional need that may be filled by a partnering contractor.

This model can take advantage of contractor expertise and result in shared program objectives of asset management, energy, water and resource efficiency, and optimized infrastructure life, forming a win-win relationship.

However, to overcome some of the challenges still prevalent, all stakeholders of the functional areas must buy in to the concept. For example, the traditional prescriptive contract language, proposed and approved by legal representatives, details all the actions and procedures the contractor must follow. In some cases, these procedures make good sense. However, they may not always be the optimal or most efficient solution—even so, the contractor is obligated to follow them. In addition, the quantity of prescriptive detail (often 100 pages or more) and requisite oversight can result in a misunderstanding of priorities and require an excess of management/contract supervision. These challenges have resulted in a new look at O&M contracts and modifications to focus more on operational efficiency and fostering contractors to look for and perform less-prescriptive and more value-added activities.

B. Management Best Practices

To manage and promote a mutual understanding between a contractor and the government owner, the following are some best practices to consider in four categories.

- Communication. It is important to establish the method, mode, and frequency of communications early in the process and to document this in the contract. There should be regularly scheduled meetings (quarterly, monthly, weekly, and/or daily) designed to facilitate communications on priority topics, systems, and equipment. These meetings can vary from quick check-ins, to high-level objectives reviews, to formal performance evaluations. The point is to establish these meetings as a regular mechanism for sharing information about what is working well, what is not, and how to improve. These meetings will also keep facility managers abreast of what the contractor is working on and provide an opportunity for the facility manager to review pertinent information such as tenant complaints, outstanding CMMS work orders, and metrics. The metrics, or key performance indicators (KPIs), should be pre-determined and documented. The use of KPIs can facilitate understanding of the priorities and should minimize cost and assure optimal performance.

- Documentation. This category includes not only the O&M contract itself, but all relevant system and equipment documentation related to data collected, equipment performance, and building documentation (drawings, manuals, etc.). This category assures all relevant documentation is accounted for, understood, and available to be reviewed regularly. Depending on the site and type of contract, the contractor may be given a form to fill out on a set frequency, to include:

- Critical facilities/infrastructure status

- Long- and short-term R&R tasks

- Site walkthrough observations

- Benchmark indicators (references are available, such as ASHRAE’s Service Life and Maintenance Cost Database)

- BAS screen outputs/energy report(s)

- Oversight. Facility owners/managers should not be shy about validating that the contract elements (e.g., preventive maintenance tasks) have been completed and done well. These oversight functions can be both regularly scheduled and unannounced and should be done both with and without contractor staff present.

- Evaluation. The frequency of contractor evaluation will vary depending on the contract size and complexity but should occur at least bi-annually if not quarterly. In addition, if the contract is with a new contractor, there may be a mandatory initial performance period. The evaluation should include any objectives and the KPIs described in the contract. All evaluation metrics should be well-defined in the contract, and the contractor should be prepared to present their progress.

C. Data Collection, Tracking, and Metrics

The type of agency and O&M contract (full coverage, full labor, preventative maintenance, etc.) tends to determine the types of data to be collected, analyzed, acted on, and used for evaluation. For modern facilities, it is important to take advantage of available computerized and metering systems to collect, store, trend, and analyze data. These systems will typically include some form of an energy management and control system, a whole-building meter data management system, and/or a CMMS. Using the data from these systems to improve maintenance management and operational efficiency is critical to effective O&M. Highlighting the availability of and access to these systems, as well as the expectation of their productive use, should be a priority element within the O&M contract.

With all the data these systems can generate and store, questions arise, such as “Is the data accurate?” or “How do I prioritize?” The data provided by each available system should be listed, reviewed, evaluated, and prioritized to make sure appropriate data is compiled. Each system will have some data deemed key to the O&M program. For instance, the tracking of specific CMMS work orders can indicate trends about a piece of equipment and/or system. The trends can show operation out of design specifications, and/or a system that requires more frequent repairs, which may indicate a design malfunction and/or an R&R issue. Other key operational data includes when and how long equipment is operated and the fact that some major unit (e.g., a boiler) is cycling on and off.

To assure the data is accurate, data from all systems needs to be continuously verified and updated to make sure the results and conclusions are valid. One option to keep data updated may be to request contractor support. For example, the contractor could complete a building inventory form (updating equipment) on a specific site area(s) at select intervals to continually validate the CMMS database.

Poor maintenance adversely affects operational performance. Likewise, poor operation practices can increase the amount of maintenance required to keep equipment running. Thus, tracking and acting on prioritized key operational metrics should improve efficiency and extend the life cycle of equipment.

Best practices documents can come from many sources, such as the owner or the manufacturer. These should be compiled and shared with the contractor to facilitate an effective O&M program. This is especially important for new technology. New technology can include manufacturer recommendations as well as checklists indicating maintenance frequency (e.g., daily, weekly, quarterly, annually) of O&M tasks.

As part of a functional O&M program, staff should be engaged in their control system and equipment beyond routine preventative maintenance. To highlight this aspect in contracted maintenance, operational routines can be added to preventative routines, requiring similar documentation and verification. From a controls perspective, these operational requirements may include routinely addressing and documenting the following:

- Have occupancy patterns or space layouts changed?

- Are heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) and lighting still zoned to efficiently serve the spaces?

- Have temporary occupancy schedules been returned to original settings?

- Have altered equipment schedules or lockouts been returned to original settings?

- Is equipment short cycling?

- Are timeclocks checked monthly to assure proper operation?

- Are seasonally changed setpoints regularly examined to assure proper adjustment?

- Are new tenants educated in the proper use and function of thermostats and lighting controls?

V. Summary and Future Plans

A. Summary

This research was done to determine the current status of O&M contracts, especially those using performance-based or incentive-based contracting for O&M services. Although the research was finite because we could not evaluate every federal agency’s O&M model, one key finding was that most agencies understand the value of a partnership with an O&M contractor. The success of a partner drives the success of a federal agency in meeting its mission.

Historically, the federal government has promoted public–private partnerships to leverage resources, ignite creativity, mitigate risk, and achieve results it could not realize on its own. This trend is expected to continue with an increase in contracted services. Many of these services are contracted with the intent of establishing a sustainable partnership. However, completely breaking away from the common prescriptive contracts of the past has proven difficult. Thus, many piloted O&M models have yielded mixed results.

The mixed results indicate there is no one single action to improve contracts.

B. Future Plans

One potential path forward would be more closely evaluating public–private partnerships using performance or incentive-based contracting. The evaluation would include the culture adopted, the contract methods used, the advantages and disadvantages, KPIs employed, and lessons learned to develop a list of improvement opportunities and/or best practices to advance federal contracting toward a working, cost-effective system.

Consistent with the goal of greater contractor engagement and possibilities of performance-based contracting opportunities resides the need for documented accountability. In the O&M field, accountability can be difficult to measure. However, the development and use of O&M-specific KPIs, both leading and lagging, should be part of the public–private partnership evaluations. This will aid in productive and effective contractor engagement.

The partnering concept appears to hold value on both sides of the agreement. In this approach, contractors are encouraged to do what they do best and bring new and innovative aspects of O&M systems to the table. In addition, if a “systems approach” is used to identify a gap in knowledge or experience, they can fill that need with a “partner” contractor, making an organization whole and more effective. From the agency perspective, more engagement from the contractor affords off-loading of tasks and improved efficiency.

VI. Resources and Defined Terms

This section provides FEMP O&M best practices and ASHRAE standard practice resources for HVAC systems in commercial facilities.

A. Additional Resources

- Air-Side Economizers O&M: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/air-side-economizers

- Ground Source Heat Pump: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/ground-source-heat-pump#Maintenance%20Checklist

- Modular Boilers: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/modular-boiler-systems

- Standby Generator: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/standby-generators

- Unitary HVAC Equipment: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/unitary-hvac-equipment

- Variable Air Volume (VAV) Systems: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/variable-air-volume-systems

- Variable Speed Drives: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/variable-speed-drives

- Automatic Transfer Switches: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/automatic-transfer-switches

- Solar Water Heating Systems: https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/solar-water-heating-systems

Another good source of checklists is ANSI/ASHRAE/ACCA Standard 180-2018, Standard Practice for Inspection and Maintenance of Commercial Building HVAC Systems. The equipment and/or systems provided in this standard are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Equipment/Systems

| 5-1 Air Distribution Systems | 5-2 Air Handlers |

| 5-3 Boilers | 5-4 Chillers—Absorption |

| 5-5 Chillers—Air-Cooled | 5-6 Chillers—Water-Cooled |

| 5-7 Coils and Radiators | 5-8 Condensing Units |

| 5-9 Control Systems | 5-10 Cooling Towers and Evaporative Cooled Devices |

| 5-11 Dehumidification and Humidification Devices | 5-12 Economizers—Air-Side |

| 5-13 Engines—Microturbines | 5-14 Fans (e.g., Exhaust, Supply, Transfer, Return) |

| 5-15 Fan Coils—Hot-Water and Steam Unit Heaters | 5-16 Furnaces—Combustion Unit Heaters |

| 5-17 HVAC Water Distribution Systems | 5-18 Indoor Section Duct-Free Splits |

| 5-19 Outdoor-Air Heat-Exchanging Systems | 5-20 Package Terminal Air Conditioners/Heat Pumps (PTACs/PTHPs) |

| 5-21 Pumps | 5-22 Rooftop Units |

| 5-23 Steam Distribution Systems | 5-24 Terminal and Control Boxes (e.g., VAV, Fan-Powered, Bypass) |

| 5-25 Water-Source Heat Pump |

B. Definitions

Advanced Meters. Meters that have the capability to measure and record interval data (at least hourly for electricity) and communicate the data to a remote location in a format that can be easily integrated into an advanced metering system. The Energy Policy Act of 2005, Section 103, requires at least daily data-collection capability.

Benchmarking (Buildings/Systems). Comparing building energy performance to that of similar buildings (cross-sectional benchmarking) or its own historical performance (longitudinal benchmarking). Benchmarking may be performed at the system or component level.

Building Automation System (BAS). A system of digital controllers, communication architecture, and a user interface that monitors and controls a building’s mechanical and electrical equipment such as HVAC, lighting, fire protection, vertical transport systems, and irrigation systems. The system can be used to optimize facility operation and reduce energy consumption. Also known as a building control system or energy management system.

Building Re-tuning™. A systematic process to identify operation problems by leveraging data collected from the BAS and correcting those problems at no or low cost.

Commissioning. A systematic process of ensuring, using appropriate verification and documentation during the period beginning on the initial day of the design phase of the facility and ending not earlier than 1 year after the date of completion of construction of the facility, that all facility systems perform interactively in accordance with the design documentation and intent of the facility and the operational needs of the owner of the facility, including preparation of operation personnel. The primary goal of commissioning is to assure fully functional systems that can be properly operated and maintained during the useful life of the facility.

Computerized Maintenance Management System (CMMS). A computerized system to assist with the effective and efficient management of maintenance activities through the application of computer technology. It generally includes elements such as a computerized work order system, capabilities for scheduling routine maintenance tasks, recording and storing standard jobs, bills of materials, applications parts lists, and equipment manuals.

Cycling. The non-continuous operation of equipment.

Energy Savings Performance Contract (ESPC). An investment tool that allows organizations to procure energy savings and facility improvements with no up-front capital costs or special appropriations. An ESPC is a partnership between an organization/agency and an ESCO.

Energy Service Company (ESCO). A company that develops, designs, builds, and funds projects that save energy, reduce energy costs, and decrease O&M costs at their customers’ facilities. In general, ESCOs act as project developers for a comprehensive range of energy conservation measures and assume the technical and performance risks associated with a project.

Facilities Maintenance. The recurring day-to-day work required to preserve facilities (buildings, structures, grounds, utility systems, and installed equipment) in such a condition that they may be used for their designated purpose over an intended service life. It includes the cost of labor, materials, and parts.

Fault Detection and Diagnostics (FDD). Software products that can automatically identify (detect) deviations from normal or expected operation (faults), and resolve (diagnose) the type of problem or its location.

Indefinite Delivery, Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ). A type of contract that provides for an indefinite quantity of supplies or services during a fixed period. IDIQs are also sometimes called task orders or delivery order contracts.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). A select number of key measures that enable performance against targets to be monitored. These indicators generally fall into one of two categories:

- Leading KPIs: A measure of performance before change or degradation that is used to track future performance.

- Lagging KPIs: A measure of performance of what has already happened and how it affects the system, process, or business. Used to track past performance.

Maintenance. Any activity carried out on an asset to assure that the asset continues to perform its intended functions, or to repair the equipment.

Net-Zero. Consuming only as much energy as produced, achieving a sustainable balance between water availability and demand, and eliminating solid waste sent to landfills.

Operational Efficiency. The life-cycle, cost-effective mix of preventive, predictive, and reliability-centered maintenance technologies, coupled with equipment calibration, tracking, and computerized maintenance management capabilities, all targeting reliability, safety, occupant comfort, and system efficiency.

Operations and Maintenance (O&M). Decisions and actions regarding the control and upkeep of property and equipment.

Performance Contract. An agreement in which the success of an energy-efficiency project plays a role in determining how the contractor is compensated for managing the project. Performance contracts generally shield the project owner from losses due to a failed project, thereby reducing or eliminating risk. A successful project may reward the contractor with above-market returns as compensation for taking on the risk of failure.

Systems Thinking. A discipline for seeing wholes. Systems thinking is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing patterns of change rather than static “snapshots.” (Defined by Peter Senge, director of the Center of Organization Learning at MIT’s Sloan School of Management [The Institute for Systemic Leadership 2018].)

Utility Energy Service Contract (UESC). A limited-source contract between a federal agency and its serving utility for energy and water efficiency improvements and demand reduction.

VII. Appendices

Appendix A. Service Contract Types (PECI 1997)

Full-Coverage Service Contract

A full-coverage service contract provides 100% coverage of labor, parts, and materials, as well as emergency service. Owners may purchase this type of contract for all their building equipment or for only the most critical equipment, depending on their needs. This type of contract should always include comprehensive preventive maintenance activities for the covered equipment and systems.

If not already addressed by the contract, for an additional fee the owner can purchase R&R coverage (sometimes called a “breakdown” insurance policy) for covered equipment. This makes the contractor completely responsible for the equipment. When R&R coverage is part of the agreement, it is to the contractor’s advantage to perform rigorous preventive maintenance according to schedule because they are responsible for replacing the equipment if it fails prematurely.

This is usually the most comprehensive and most expensive agreement in terms of short-term impact on the maintenance portion of the facilities budget. However, it may be the most cost-effective in the long term, depending on the owner’s overall O&M objectives. A major advantage of a full-coverage contract is the ease of budgeting and the fact that the contractor carries most if not all of the risk. However, if the contractor is not reputable or underestimates the condition of the equipment they are ensuring, they may do only enough preventive maintenance to keep the equipment barely running until the end of the contract period. Also, when a company underbids the work to win the contract, they may attempt to break the contract early if they foresee a high probability of one or more catastrophic failures occurring before the end of the contract.

- Benefits

- Most comprehensive and complete contract available

- Reduced recurring administrative expenses

- Reduced risk profile of owner—contractor assumes most/all risk.

- Challenges

- Most expensive of the contracting options

- Finding a reputable contractor that fully understands and is capable of the scope

- Making certain all appropriate maintenance activities are completed when needed.

Full-Labor Service Contract

A full-labor service contract covers 100% of the labor to repair, replace, and maintain most mechanical equipment. The owner is required to purchase all equipment and parts. Although preventive maintenance and operation may be part of the agreement, actual installation of major plant equipment (such as a centrifugal chiller, boilers, and large air compressors) is typically excluded from the contract. Risk and warrantee issues usually preclude anyone but the manufacturer from installing this type of equipment. Also, how emergency calls are dealt with in this arrangement varies. The cost of emergency calls may be factored into the original contract, or the contractor may agree to respond to an emergency within a set number of hours, with the owner paying separately for the emergency labor. Some preventive maintenance services are often included in the agreement along with minor materials such as belts, grease, and filters.

This is the second-most-expensive contract in terms of short-term impact on the maintenance budget. This type of contract is usually only advantageous for owners of very large buildings or multiple properties, allowing them to buy in bulk and thereby obtain equipment, parts, and materials for much less than the average building owner. For owners of smaller-to-medium-size buildings, cost control and budgeting become more complicated with this type of contract because labor is the only constant. Because they are only responsible for providing labor, the contractor assumes less risk with this type of contract than with a full-coverage contract.

- Benefits

- Full-labor coverage for maintenance, repair, and replacement

- Potential for better cost control on equipment cost and procurement

- Lower cost compared to full-service contract.

- Challenges

- Additional assumption of risk with equipment procurement

- Second-most-expensive contracting option.

Preventive Maintenance Service Contract

The preventive maintenance service contract is generally purchased for a fixed fee and includes several scheduled and rigorous preventive maintenance activities such as changing belts and filters, cleaning indoor and outdoor coils, lubricating motors and bearings, cleaning and maintaining cooling towers, testing control functions and calibration, and painting for corrosion control, among others. Generally, the contractor provides the materials such as filters, belts, grease, paint, and coil cleaner as part of the contract. This type of contract is popular with owners and is widely sold. The contract may or may not include arrangements for repairs or emergency calls.

The main advantage of this type of contract is that it is initially less expensive than either the full-service or full-labor contract and provides the owner with an agreement that focuses on quality preventive maintenance. However, budgeting and cost control for emergencies, repairs, and replacements is more difficult because these activities are often done on a time-and-material basis. With this type of contract, the owner takes on most of the risk. Also, unless the owner knows what preventive maintenance activities are most important and how often the activities should be performed (given the equipment condition and the surrounding environment), they could end up with a contract that addresses substantially more or less than what they really need. For example, if the building is in a particularly dirty environment, the outdoor cooling coils may need to be cleaned two or three times during the cooling season instead of just once at the beginning of the season. It is important to understand how much preventive maintenance is enough to realize the full benefit of the contract.

The owner or manager needs to be aware that some contractors’ preventive maintenance programs more closely resemble the inspection service contract described below. Not all preventive maintenance service contracts contain the same rigor. When obtaining bids, compare the level of service each agreement intends to provide, as well as the price.

- Benefits

- Offers cost savings over either of the full-service offerings

- Focus on preventive maintenance offers greater direction and administrative savings.

- Challenges

- Owner assumes all the risk for R&R activities

- Owner-incurred costs of R&R are related to the quality of contracted preventative maintenance.

Inspection Service Contract

An inspection service contract, also known in the industry as a “fly-by” contract, is purchased by the owner for a fixed annual fee and includes a fixed number of periodic inspection activities. Inspection activities are much less rigorous than preventive maintenance. Simple tasks such as changing a dirty filter or replacing a broken belt are performed automatically, but for the most part, inspection means looking to see if anything is broken or is about to break and reporting it to the owner. The contract may or may not include a limited number of materials (belts, grease, filters, etc.) to be provided by the contractor or an agreement regarding other service or emergency calls.

From a short-term perspective, this is the least expensive type of contract. However, this may also be the least effective type of contract, because it is not always a moneymaker for the contractor, but rather is viewed as a way to maintain a relationship with their customer. With this “foot in the door” arrangement, the contractor is more likely to be called when a breakdown or emergency occurs. They can then bill on a time-and-material basis. Low cost is the main advantage to this type of contract, and it is thought to be most appropriate for smaller buildings with simple mechanical systems.

- Benefits

- Least expensive of the standard O&M contract types

- Easier to manage with a fixed fee and reduced scope.

- Challenges

- Lowest rigor of all contract types

- Focus is on reactive maintenance, which typically is not cost-effective

- Higher potential for catastrophic failures.

Performance-Based/End-Results Contracting

Performance-based, or end-results, contracts are one of the newer concepts in service contracting, although the concept has been prevalent for many years. With this type of contract, the outside contractor takes over the operational risk for a particular end result such as comfort—in this case, comfort is the product being bought and sold. As a simple example, the owner and contractor agree on a definition for comfort and a way to measure whether the results are achieved. Comfort may be defined as maintaining the space temperature throughout the building between 72 and 74 °F for 95% of the annual occupied hours. The contract payment schedule is based on how well the contractor achieves the agreed-upon objectives.

This type of contract may be appropriate for owners who have sensitive customers or critical operational needs that depend on maintaining a certain level of comfort or environmental quality for optimum productivity. How risk is shared between the owner and contractor depends on what type of or how many end results are purchased. If comfort defined by dry-bulb temperature is the only end result required, then the owner takes on the risk for ameliorating other problems such as indoor air quality, humidity, and energy use issues. Maximum contract price is tied to the amount and complexity of the end results purchased.

The Federal Acquisition Regulation defines this under Performance Work Statements (FAR subpart 37.602) as:

- A performance work statement (PWS) may be prepared by the government or result from a statement of objectives prepared by the government where the offeror proposes the PWS.

- Agencies shall, to the maximum extent practicable:

- Describe the work in terms of the required results rather than either "how" the work is to be accomplished or the number of hours to be provided.

- Enable assessment of work performance against measurable performance standards.

- Rely on the use of measurable performance standards and financial incentives in a competitive environment to encourage competitors to develop and institute innovative and cost-effective methods of performing the work.

Under this guidance, a performance-based contract can be developed that allows the risk for outcomes to squarely reside on the contractor. The net benefit to the owner results from expected cost reductions in specification development, implementation, supervision, and evaluation. Performance-based contracts do require periodic performance measurements to assure the required “results” have been delivered/achieved. In the above example of delivered “comfort,” this could include customer feedback (or complaint) tracking and possible temperature trending with a BAS.

- Benefits

- Encourages contractor to deliver a result that makes the best use of their expertise and efficiencies versus prescribed steps and processes

- Potential owner savings resulting from reduced costs of specification development, implementation, supervision, and evaluation.

- Challenges

- Defining the most suitable facilities, systems, and equipment appropriate for performance-based contracting

- Developing the measurable standards to which a contractor will be held

- Defining the financial structure to be acceptable and equitable for both the contractor and owner.

As of this writing, there have not been any widely publicized successes in performance-based O&M contracting in the federal government. This does not mean they do not exist. One possible next step is to develop a demonstration or pilot implementation based on this concept.

Appendix B: Contract Award Types (OMB 1998)

Fixed-Price/Firm-Fixed-Price

Fixed-price contracts provide for a firm price or, in appropriate cases, an adjustable price. Fixed-price contracts providing for an adjustable price may include a ceiling price, a target price (including target cost), or both. Unless otherwise specified in the contract, the ceiling price or target price is subject to adjustment only by operation of contract clauses that provide for equitable adjustment or other revision of the contract price under stated circumstances.

A firm-fixed-price contract provides for a price that is not subject to any adjustment based on the contractor’s cost experience in performing the contract. This contract type places upon the contractor maximum risk and full responsibility for all costs and resulting profit or loss. It provides maximum incentive for the contractor to control costs and perform effectively and imposes a minimum administrative burden on the contracting parties.

The contracting officer may use a firm-fixed-price contract in conjunction with an award-fee incentive and performance or delivery incentives when the award fee or incentive is based solely on factors other than cost. The contract type remains firm-fixed-price when used with these incentives.

Application: Fixed-price contracts are appropriate for services that can be objectively defined in the solicitation and for which risk of performance is manageable. For such acquisitions, performance-based statements of work, measurable performance standards, and surveillance plans are ideally suited. The contractor is motivated to find improved methods of performance in order to increase its profits.

- Benefits

- Contract risk is largely borne by the contractor based on their pricing

- Offers stability and predictability to both the owner and contractor

- Can offer a hedge against inflation based on economy and contract length.

- Challenges

- Contract needs to be well defined and have a plan to cover areas/topics omitted or missed in the contract

- Contractor assuming the most risk can result in a higher-cost contract.

Cost Reimbursement/Cost Plus

Cost-reimbursement (also known as cost plus) contracts provide for payment of allowable incurred costs to the extent prescribed in the contract. These contracts establish an estimate of total cost for the purpose of obligating funds and establishing a ceiling that the contractor may not exceed (except at its own risk) without the approval of the contracting officer.

Application: Cost-reimbursement contracts are appropriate for services that can only be defined in general terms or for which the risk of performance is not reasonably manageable.

- Benefits

- Can result in higher quality because the contractor has incentive to use the best labor and materials

- Can be less expensive than a fixed-price contract because the owner assumes the risk of higher-price materials

- Less chance of having the project overbid.

- Challenges

- Owner assumes risk of increasing cost

- Additional oversight to assure costs are being managed properly by contractor.

Cost Reimbursement/Cost Plus

A time-and-materials/labor-hour contract provides for acquiring supplies or services based on direct labor hours at specified fixed hourly rates that include wages, overhead, general and administrative expenses, and profit and/or actual cost for materials.

Application: A time-and-materials/labor-hour contract may be used only when it is not possible at the time of placing the contract to accurately estimate the extent or duration of the work or to anticipate costs with any reasonable degree of confidence.

- Benefits

- Contracting certainty because payments are a set amount for the time and materials to complete the project

- Relative ease in negotiating terms and conditions because these are typically established up-front

- Cost control on billable hours and resulting schedule certainty.

- Challenges

- Additional levels of management and accounting are critical for financial management and control

- Establishing not-to-exceed values for all contract elements.

Fixed-Price Contract with Award Fees

A variation of the above fixed-price contract adds an award-fee option. Award-fee provisions may be used in fixed-price contracts when the owner wishes to motivate a contractor and other incentives cannot be used because contractor performance cannot be measured objectively. Such contracts shall establish a fixed price (including normal profit) for the effort. This price will be paid for satisfactory contract performance. Award fee earned (if any) will be paid in addition to that fixed price. Award-fee contracts are a type of incentive contract.

Application: An award-fee contract is suitable for use when:

- The work to be performed is such that it is neither feasible nor effective to devise predetermined objective incentive targets applicable to cost, schedule, and technical performance.

- The likelihood of meeting acquisition objectives will be enhanced by using a contract that effectively motivates the contractor toward exceptional performance and provides the owner with the flexibility to evaluate both actual performance and the conditions under which it was achieved.

- Any additional administrative effort and cost required to monitor and evaluate performance are justified by the expected benefits as documented by a risk and cost benefit analysis.

The amount of award fee earned shall be commensurate with the contractor’s overall cost, schedule, and technical performance as measured against contract requirements in accordance with the criteria stated in the award-fee plan. An award fee shall not be earned if the contractor’s overall cost, schedule, and technical performance in the aggregate is below satisfactory. The basis for all award-fee determinations shall be documented in the contract to include, at a minimum, a determination that overall cost, schedule, and technical performance in the aggregate is or is not at a satisfactory level. This determination and the methodology for determining the award fee are unilateral decisions made solely at the discretion of the owner. Table B.1 provides a sample of typical award-fee ratings and awards.

- Benefits

- Establishes a mechanism to encourage the contractor to go beyond the elements in the defined contract and toward exceptional performance

- Allows the contractor to be innovative in contract execution

- Facilitates dialog between owner and contractor on options and actions, resulting in better performance.

- Challenges

- Requires definition of award criteria

- Requires formal evaluation to determine award-fee amounts

- Can require greater interaction and oversight as program initiates.

Table B.1. Sample Award-Fee Ratings and Awards

Award-Fee Adjectival Rating | Award-Fee Available | Description |

| Excellent | 91–100% | Contractor has exceeded almost all the significant award-fee criteria and has met overall cost, schedule, and technical performance requirements of the contract in the aggregate as defined and measured against the criteria in the award-fee plan for the award-fee evaluation period. |

| Very Good | 76–90% | Contractor has exceeded many of the significant award-fee criteria and has met overall cost, schedule, and technical performance requirements of the contract in the aggregate as defined and measured against the criteria in the award-fee plan for the award-fee evaluation period. |

| Good | 51–75% | Contractor has exceeded some of the significant award-fee criteria and has met overall cost, schedule, and technical performance requirements of the contract in the aggregate as defined and measured against the criteria in the award-fee plan for the award-fee evaluation period. |

| Satisfactory | No Greater Than 50% | Contractor has met overall cost, schedule, and technical performance requirements of the contract in the aggregate as defined and measured against the criteria in the award-fee plan for the award-fee evaluation period. |

| Unsatisfactory | 0% | Contractor has failed to meet overall cost, schedule, and technical performance requirements of the contract in the aggregate as defined and measured against the criteria in the award-fee plan for the award-fee evaluation period. |

Appendix C: Model Comparison (GSA 2021)

VIII. References

10 CFR 436 subpart B, Methods and Procedures for Energy Savings Performance Contracting. Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-10/chapter-II/subchapter-D/part-436/subpart-B

42 U.S.C. 8287 et seq., Authority to enter into contracts. U.S. Code, as amended. http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title42-section8287&num=0&edition=prelim

42 U.S.C. 8253 et seq., Energy and water management requirements. U.S. Code, as amended. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?hl=false&edition=prelim&req=granuleid%3AUSC-2012-title42-section8253&f=treesort&fq=true&num=0#sourcecredit

EERE. 2011. What is Energy Savings Performance Contracting (ESPC)? U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Washington, D.C. https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2014/06/f16/T2_ICF_FS1_WhatisESPC_FINAL_052311.pdf

EERE. n.d.(a). About the Federal Energy Management Program. U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Federal Energy Management Program, Washington, D.C. https://www.energy.gov/eere/femp/about-federal-energy-management-program

EERE. n.d.(b). Federal UESC Process Phase 5: Post-Acceptance Performance. U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Federal Energy Management Program, Washington, D.C. https://www.energy.gov/eere/femp/federal-uesc-process-phase-5-post-acceptance-performance

EERE. n.d.(c). Water Metering Resources. U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Federal Energy Management Program, Washington, D.C. https://www.energy.gov/eere/femp/water-metering-resources

EERE. 2010. Release 3.0: Operations and Maintenance Best Practices. A Guide to Achieving Operational Efficiency. U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Federal Energy Management Program, Washington, D.C. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2013/10/f3/omguide_complete.pdf

EO 13800, Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure. May 12, 2021. The White House, Washington, D.C. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/05/12/executive-order-on-improving-the-nations-cybersecurity/

EO 14057, Catalyzing America’s Clean Energy Economy Through Federal Sustainability. December 8, 2021. The White House, Washington, D.C. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/12/08/executive-order-on-catalyzing-clean-energy-industries-and-jobs-through-federal-sustainability/

FAR part 16, Types of Contracts. Federal Acquisition Regulation. https://www.acquisition.gov/far/part-16

FAR subpart 23.2, Energy and Water Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Federal Acquisition Regulation. https://www.acquisition.gov/far/subpart-23.2

FAR subpart 37.602, Performance work statement. Federal Acquisition Regulation. https://www.acquisition.gov/far/37.602

Federal ESPC Steering Committee. 2013. Planning and Reporting for Operations & Maintenance in Federal Energy Saving Performance Contracts. U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Federal Energy Management Program, Washington, D.C. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2013/10/f3/planning_om_espcs.pdf

Forbes. 2020. The Role of Systems Thinking in Organizational Change and Development. Forbes Coaches Council, Council Post by Jonathan H. Westover, June 15, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2020/06/15/the-role-of-systems-thinking-in-organizational-change-and-development/?sh=27e8fc352c99

GSA. 2021. Welcome. Opportunities in Construction, Facilities, and Maintenance: Take a Virtual Walk with GSA’s Public Buildings Service. Presented at Small Business Works 2021 Virtual Event. https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/Opportunities%20in%20Construction%20Facilities%20and%20Maintenance%20-%20508%20FINAL.pptx

OMB. 1998. A Guide to Best Practices for Performance-Based Service Contracting. Final Edition, 1998. Office of Federal Procurement Policy, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, Washington, D.C. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/procurement_guide_pbsc

OMB. 1998. Office of Federal Procurement Policy Performance-Based Service Acquisition. Office of Management and Budget, Office of Federal Procurement, Washington, D.C. Final Edition; October 1998; https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/procurement_guide_pbsc

PECI. 1997. Operation and Maintenance Service Contracts: Guidelines for Obtaining Best-Practice Contracts for Commercial Buildings. Portland Energy Conservation Inc., Portland, OR. https://www.energystar.gov/sites/default/files/buildings/tools/Operations%20and%20Maintenance%20Service%20Contracts_0.pdf

PNNL. 2021a. Re-tuning Buildings. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA. https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/re-tuning-buildings

PNNL. 2021b. OMETA: An Integrated Approach to Operations, Maintenance, Engineering, Training, and Administration. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA. https://www.pnnl.gov/projects/best-practices/ometa-integrated-approach-operations-maintenance-engineering-training-and-administration

Public Law 103-355, Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994. 103rd Congress (1993-1994), Washington, D.C. https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/senate-bill/1587

Public Law 109-58, Energy Policy Act of 2005. 109th U.S. Congress (2005-2006), Washington, D.C. https://www.congress.gov/109/plaws/publ58/PLAW-109publ58.pdf

Public Law 111-308, Federal Buildings Personnel Training Act of 2010. 111th Congress (2009-2010), Washington, D.C. https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/senate-bill/3250?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22Performance%22%2C%22measurement%22%5D%7D&s=1&r=11

Public Law 113-283, Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014. 113th Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/2521

The Institute for Systemic Leadership. 2018. The historical link between systems thinking and leadership. Farnham, Surrey, UK.

https://www.systemicleadershipinstitute.org/the-historical-link-between-systems-thinking-and-leadership/#:~:text=Senge%20describes%20systems%20thinking%20as,The%20first%20is%20efficiency