PNNL Hosts Workshop Exploring Strategies (and Alternatives) for the U.S. Copper Supply Chain

Stakeholders convene for a conversation on copper's criticality

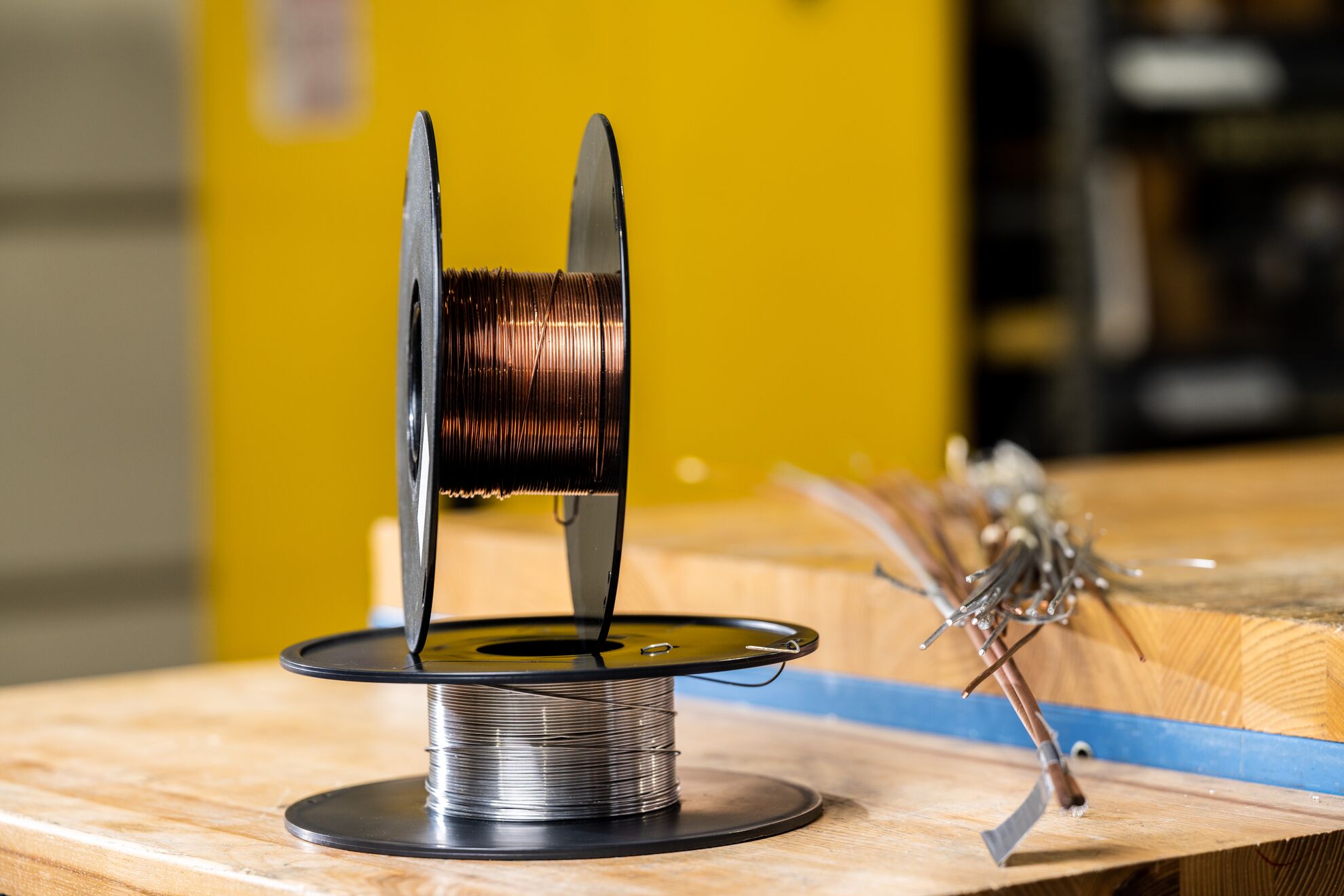

The AC2.0 workshop brought together U.S. copper stakeholders to discuss supply chain strategies.

(Photo by Andrea Starr | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory)

This summer, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) hosted the inaugural “As Conductive As Copper” (AC2.0) workshop, bringing together industry leaders, government program managers, researchers, and investors at the PNNL’s campus in Richland, Washington, for a collaborative conversation on the future of the U.S. copper supply chain.

An increasingly critical material for energy dominance

“Copper is the nervous system of our electric grid,” said Keerti Kappagantula, AC2.0’s organizer and leader of PNNL’s Functional Materials and Enabling Technologies team. “It’s needed everywhere: every electrical system, every device, every data center.”

Amid booming investment in artificial intelligence, computing, and electrification, domestic copper demand is rapidly increasing: the International Energy Agency projects an approximately 40 percent increase in copper demand by 2040.

But global copper mining is barely keeping up with current demand—and there’s another problem.

“In the United States, we specifically rely on a couple of countries for our copper imports,” Kappagantula said. “That creates a huge supply chain issue.”

Copper’s importance to U.S. energy systems—combined with its complex, high-risk supply chain—led the Department of Energy to classify the metal as a critical material for energy in 2023.

“We definitely need more copper—a lot of it,” Kappagantula said.

A meeting of the minds on copper supplies

At AC2.0, stakeholders across the copper supply chain explored strategies for bolstering the U.S. copper supply chain, covering everything from mining to manufacturing.

Some ideas—such as increasing domestic mining and smelting capacity—were acknowledged as necessary, but came with big caveats, such as long lead times and high capital investment costs.

“While we’re all trying to mine more copper, smelt more copper, refine more copper, we also need to advance alternatives,” Kappagantula said.

Throughout the workshop, there was broad agreement on the need to pursue strategies beyond building more mines and smelters, including the development of copper alternatives to ease demand and improved copper upcycling methods to take advantage of unused domestic scrap copper.

What’s as conductive as copper?

“In many industries, if a material’s supply chain is impeded, they’ll ramp up the supply of a viable substitute,” she explained. But copper is so conductive—and so widely used—that finding a viable substitute with a secure domestic supply is extremely challenging; the best affordable alternative, aluminum, is only 60 percent as conductive as copper.

At PNNL, Kappagantula and her colleagues are finding ways to tackle this challenge by using advanced manufacturing techniques like solid phase processing.

Using these techniques, PNNL researchers create composite materials (such as aluminum-graphene and copper-graphene) that have significantly improved conductivity. These “ultra-conductors” require less copper, enabling more productive use of U.S. copper supplies.

During the workshop, attendees had the chance to tour PNNL’s Shear Assisted Processing and Extrusion (ShAPE) capabilities, which can produce ultra-conductors in several different forms.

There was also interest in another alternative pathway: copper scrap.

“The United States has a lot of post-manufacturing, industrial, and post-consumer copper scrap—about half of which gets exported,” Kappagantula said. “But right now, you can’t just melt copper scrap and use it again. You have to refine it, which means that smelting capacity becomes a bottleneck.”

At AC2.0, attendees showed interest in pursuing research in areas like smelting-free reuse of copper scrap to alleviate that burden. Here, again, advanced manufacturing can help: PNNL researchers have proven the potential for smelting-free reuse of scrap metal for another critical material—aluminum.

“Copper alternatives exist today—just not at the necessary scales and price points,” said Cindy Powell, chief science and technology officer for PNNL’s Energy and Environment Directorate. “With the kind of collaboration we saw today between industry, government, and research, we’re on the right track to produce more copper and manufacture materials that are as conductive as copper right here in the United States—but more research and development will be needed.”

Published: September 4, 2025