Atmospher Sci & Global Chg

Research Highlights

August 2016

Sugar Hitches a Ride on Organic Sea Spray

Sticky organic molecules hop aboard oily floaters and may influence the amount of sunlight reflected by marine clouds

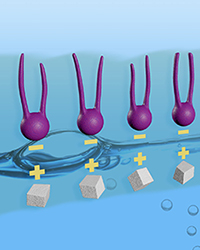

Floater Follow-up Scientists are learning more about chemical interaction mechanisms that may be responsible for the high amount of sugar-like material found in sea spray produced from ocean bubbles that burst and launch the tiny particle hitchhikers into the atmosphere. (See sidebar: Fatty acids and saccharides, ahoy!) Ultimately, they will learn how these particles impact the brightness of the cloud layers formed above the ocean, which have an effect on the Earth’s climate. Graphic by Nathan Johnson at PNNL.

Exiting the airport, travelers catch a taxi, Uber, or bus ride to their next stop. Seafaring sugar molecules floating near the ocean's surface take a similar tack. Instead of taxis, they hitch a ride on oily molecules floating by.

Results: Researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Montana State University, and Los Alamos National Laboratory found this "sticky" strategy not only shields these molecules from their soluble nature, it explains the discrepancies between models that predict sea spray's organic enrichment and the actual measurements of sea spray aerosol composition.

The study's findings, published in Geophysical Research Letters, may explain how so many soluble sugars find their way into sea spray, and provide clues to how they may affect the amount of sunlight reflected by sea-spray-seeded clouds.

Why It Matters: Sugar molecules (saccharides) are normally soluble in water. Yet, somehow, they make their way into sea-spray particles that are tossed into the atmosphere by breaking waves, eventually helping seed low-lying marine clouds. These clouds have a large role in the climate because they regulate the amount of sunlight that hits the ocean surface—the largest heat sink on the planet. By solving the mechanistic mystery by which sugars and other organic matter in sea spray aerosol, such as these sugars, is emitted to the atmosphere, scientists will be better able to simulate its impacts on the climate. This information allows better estimations of the amount of sunlight that is reflected by clouds, which has a cooling effect on the Earth.

Methods: Scientists are interested in the composition of particles tossed into the atmosphere by sea spray, a large source of water vapor helping form clouds. What are these particles that affect marine clouds? Researchers who analyze sea spray samples collected onboard ships found that they contain a large amount of saccharides (sugar-like molecules). However, because saccharides easily dissolve in water, it was unclear how this material survived to enter the spray.

A team of researchers investigated the water surface interactions between saccharides and fatty acids—oily molecules that are insoluble in water. Montana State University researchers and EMSL staff performed spectroscopy experiments at the EMSL facility and showed that saccharides can adsorb (stick) to the bottom of a layer of fatty acids that coat the water surface. This adsorption causes an increased amount of saccharide molecules to be present at the surface. When the layer of fatty acids was not present, the saccharide molecules dissolved in the water. Because sea spray aerosol forms from the surface layer of ocean water, mechanisms similar to the one investigated in this study could increase the amount of organic matter emitted in sea spray.

Using a model developed at PNNL and Los Alamos, researchers tested the sensitivity of modeled sea spray composition to this mechanism. They found that if the molecules adsorb strongly enough, the amount of organic matter emitted in sea spray could be substantially increased. These organic matter emissions could potentially impact the amount of sunlight that is reflected by clouds that are influenced by this spray.

What's Next? Researchers suggest further experiments to test interactions of additional organic molecules that reflect the range of chemistry occurring in the ocean's surface waters. They want to identify whether the interactions studied in surface films will affect the composition of artificially generated sea spray aerosol.

Acknowledgments

Sponsors: The research was partially supported by the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research for the Regional & Global Climate Modeling Program. Partial support was provided by the National Science Foundation. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic energy research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information please visit http://science.energy.gov.

User Facility: EMSL, the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE Office of Science user facility sponsored by the Department of Energy's Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at PNNL

Research Team: Susannah M. Burrows, Li Fu, and Hongfei Wang, PNNL; Eric Gobrogge, Katie Link and Rob Walker, Montana State University; and Scott M. Elliott, Los Alamos National Laboratory

Research Area: Climate and Earth Systems Science

Reference: Burrows SM, E Gobrogge, L Fu, K Link, SM Elliott, H Wang, and R Walker. 2016. "OCEANFILMS-2: Representing Co-adsorption of Saccharides in Marine Films and Potential Impacts on Modeled Marine Aerosol Chemistry." Geophysical Research Letters, in press online. DOI: 10.1002/2016GL069070

Related Highlights: Sea Critters Rule the Clouds; Born by Bubbles, Destined for Clouds; Bubbling to the Top